Design Q&A: Maurice Woods

Through mentoring young students of color, Inneract Project is addressing design’s homogeneity and bringing essential voices into the field.

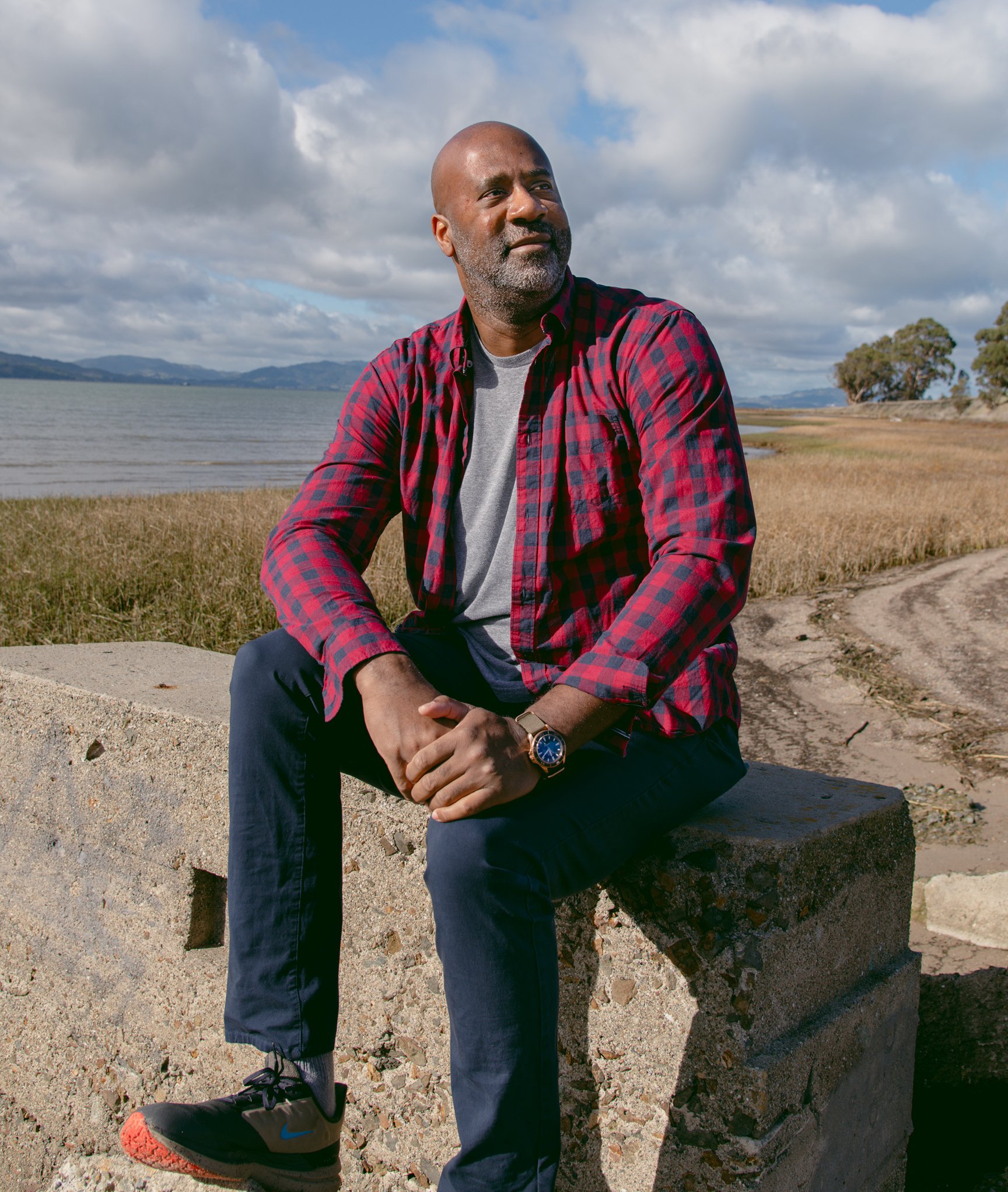

Maurice Woods photographed at Point Pinole Regional Shoreline Park, a frequent destination during the pandemic.

As a Black student studying design in the early 1990s, Maurice Woods noticed a significant absence in his classes: there were never any Black designers featured in textbooks or classroom lectures. So for a class assignment, Woods conceived a radical if straightforward initiative: he would create a mentorship program—called Inneract Project—for young people of color, so they could learn about design, experience its benefits, and consider it as a future career. Mentorship and representation were the core components to the effort, through which Woods would seek, in the long term, to shift the design discipline’s lack of diversity and disconnection from communities of color. At his first session, held at a West Seattle community center in 2004, he guided three students through exploratory design exercises.

Woods, now a principal design manager at Microsoft, has been leading the nonprofit ever since. Inneract offers an ongoing series of volunteer-led design classes for Black and brown youth. Woods describes the effort as “supporting and empowering generations of Black and brown designers, guiding them toward successful pathways in design”—ensuring that the design field encompasses the full diversity of perspectives. Over 10,000 students have been impacted by the program, which empowers them to create hands-on projects.

To engage young people in the design mindset, Inneract tailors its projects to connect to what students are excited about in their day-to-day lives. “When students are bringing their world into the design,” says Woods, “they can start to understand it and articulate their perspective and work a lot more powerfully than if they’re trying to approach a project in a manner where it doesn’t jibe, or they don’t understand the context for why something is important to them.”

The Inneract students’ creations reveal the relevance of design to context, community, and personal identity. One student conceived a cane-walker hybrid as an assistive device for her grandmother. Other Inneracters have sketched out ideas for smartwatches, a school lunch app, and an energy conservation campaign. Student empowerment and pride are evident in projects like an ebony light fixture that has the words “Black Is Beautiful” cut into the side. Recent program alums have gone on to schools such as Parsons School of Design, UCLA, and CalArts, while participants from the early years now work at companies such as Facebook and Nike.

The design field is no exception to the homogeneously disproportionate whiteness of fields ranging from engineering to medicine. A 2021 AIGA survey showed that African Americans made up 4.9% of its design industry respondents but 12.6% of the US labor force. Hispanic/Latinx design respondents were 9% of the survey but 18% of the labor force. In the realm of mentorship, a 2021 study of 341 US colleges showed that out of 7,686 college-level art/design instructors, only 117 were Black women (1.5%) and 187 were Black men (2.4%).

This lack of representation reveals the impact of racism and inequitable access to resources and education; it also prevents talented creatives from entering the field, blocks economic opportunity, and results in design work that erases perspectives or does not give voice to communities of color. Yet while many companies expressed their diversity bona fides following the 2020 murder of George Floyd, those statements were empty or the initiatives, if they existed, have been deprioritized. “It’s not the same as it used to be, but those efforts are still critically important,” says Woods. “And that’s where it’s difficult for us as an organization—because we already had to convince people that design is important. Obviously diversity in design is also equally important.”

While continuing to organize introductory workshops and events, Inneract is now focusing on two main offerings: a four-week summer design camp, beginning July 2024, which gives participants evocative creative experiences. The second project, Uplift, is an online platform that connects emerging designers of color with a community of mentors from design firms, corporations, and other organizations, who offer career insight, portfolio reviews, mock interviews, and more. College students and professors can also use Uplift to seek out designers for class crits and talks.

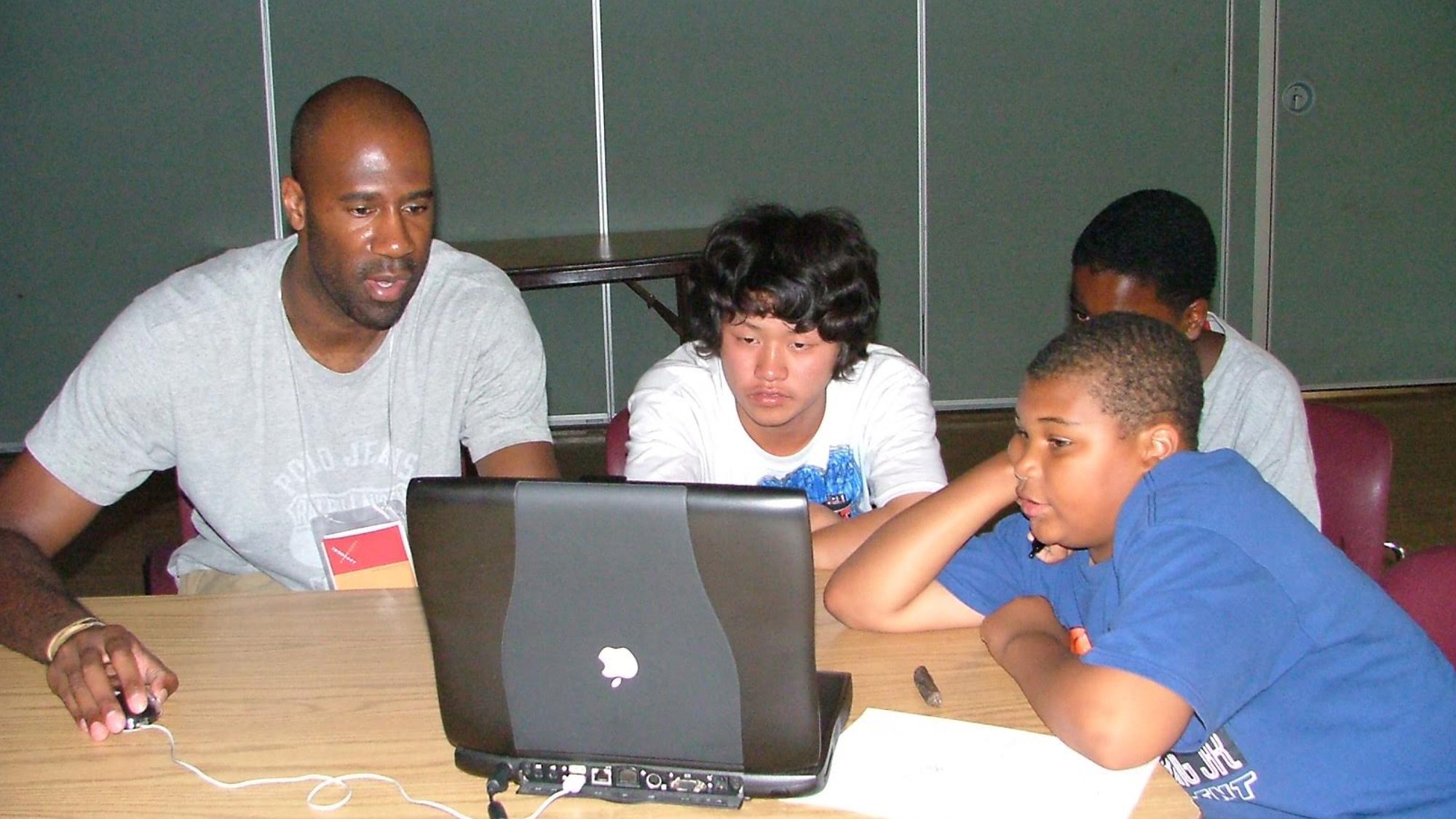

Maurice Woods mentors students at one of the first Inneract Project sessions, held at West Seattle’s Delridge Community Center in 2004.

Woods is continually advocating for greater diversity in design, which includes pushing for change in the hiring and recruiting paradigms at companies like Microsoft, Google, and Apple. Tech companies often recruit students from certain top-tier schools, but “our Black and brown kids are not going there,” says Woods, who notes that trends point to fewer Black and brown students attending elite colleges. “All the data supports that. They’re not even going to the top schools in general, let alone top design schools.” Through educating businesses that students of color are studying design at community colleges, trade schools, and boot camps, Woods hopes to help them “shift how they recruit and find students.”

Systemic barriers are one quandary that Inneract addresses; another is how to engage students and families in the most effective way. In its programming, the organization has to respond to fundamental challenges in communities of color, including financial and socioeconomic barriers. Noting that some Inneract students don’t have regular meals except when they eat at school, Woods asks, “How do you teach design in a scenario where you’re encountering students that have all these barriers?” Inneract answers that question by always offering programs free-of-charge and serving food; some students receive stipends for attending ongoing classes. “We’ve been very intentional about our work not being just about education, but also thinking about all the other barriers that people of color face in order to be able to sit down, concentrate, and learn what we’re trying to teach them,” notes Woods. “It’s bigger than just teaching design.”

Woods introducing a panel discussion organized by Inneract Project for an event at SFJAZZ Center in 2015.

In the 1972 film Design Q&A, French curator Madame L’Amic presents Ray and Charles Eames with a series of archetypal questions about design’s meaning and purpose. As part of an ongoing feature in Kazam!, we posed those same questions to Maurice Woods.

Q: What is your definition of design?

A: Design is a privilege, or a method for which all life is based on. Design is the manifestation of a thought, an idea or a need to develop, innovate, or create something that makes a process move forward—or to make our lives better, more suitable, or more sustainable. Everything in this world is designed, from the trees to the mountains to our bodies. Everything’s intentional. We need the clouds in the sky and the bugs and the animals, and everything on earth—it’s all of purpose. Design follows that same pattern. The reason why we design as people is the same reason why bees make honey or birds build nests for their eggs or spiders create webs. All of humankind designs—it is part of who we are. We as people are part of a process, and we have our own mode of designing.

Q: Is design an expression of art?

A: Design is an expression of life.

Q: What are the boundaries of design?

A: There are no boundaries except for the boundaries that we create as people.

Q: Is design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

A: No. I think that everything is connected. And one way that this manifests is through the instinctive nature of design. While not everybody has the creative talent for drawing, typography, or generating ideas in a particular manner, I believe that everybody has the capacity to design based on what they learn about the task at hand.

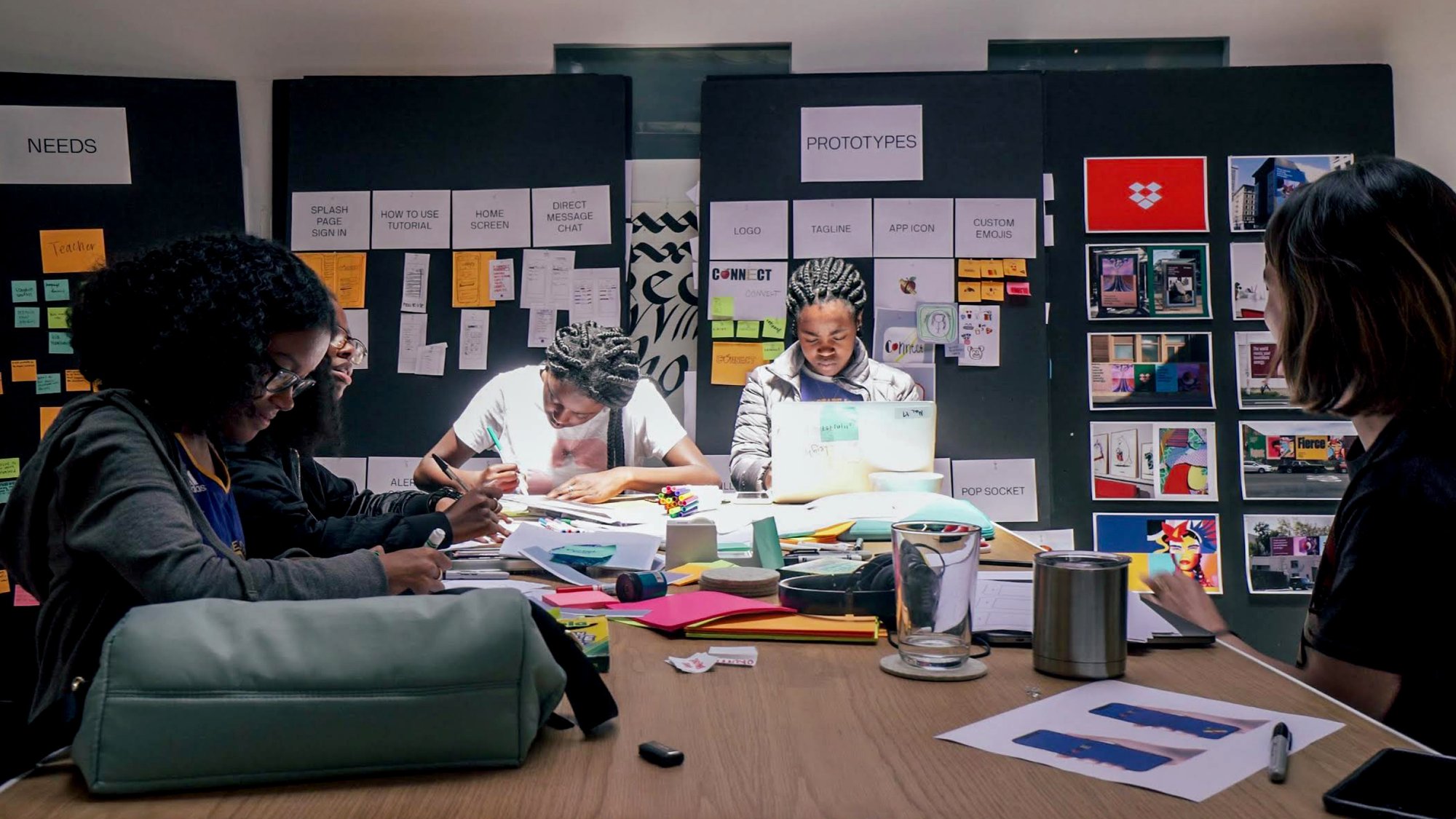

Students work on an Inneract Project design exercise as mentors observe.

Q: Is design a creation of an individual or group?

A: Design is the creation of either an individual or a group. But we as individuals come with our own set of contexts, and by means of that context, we either innovate on our own or we influence the people around us. For example, another person and I may come from different worlds, yet when we come together to address a problem, we solve it by building on our understanding of our own context and outlook. Together we create something that’s more powerful than what is created by just one of us.

Q: Is there a design ethic?

A: Yes. What I value the most is thinking inclusively about the work that we do. Everything that we do as a people is in service to humanity and the entities that live on this Earth. So being inclusive and thinking beyond your own personal gains and thoughts is for me what it means to be a good citizen of design. And that includes having an ethic about the way that design represents different communities.

Design has not always done a great job at leading in this space: There are years and years of visual representation of people of color that have been manifested in ads and other media—and these images function as programming. For a very long time, only white people were in commercials, or only white people were featured on packaging. Or Black people were only depicted in a certain way—raunchy, loud, and wearing gold chains. The psychology of visual images plays a part in people being able to understand the true representation of people. When you are seeing these visual images all the time and you’re programmed so that they start to mean something to you psychologically, it starts to generate a certain perspective or a level of prejudice, bias, or misunderstanding—and then that’s represented in how you act towards those people.

Visual images and visual representations are important, and designers are at the table when it comes to creating them. I’m not saying that we’re the only ones, but it is a big portion of the work that we do, and that includes graphic design as well as the UI and user experience. Those are all things that people are interacting with all the time, and those influence how people perceive certain processes and think about our world.

As the founder and owner of this organization that’s teaching kids of color, my job and my ethic is: How do we get the perspective right? How do we get people of color in design so that they’re able to put their perspective into any process so that misunderstanding and misrepresentation doesn’t come through?

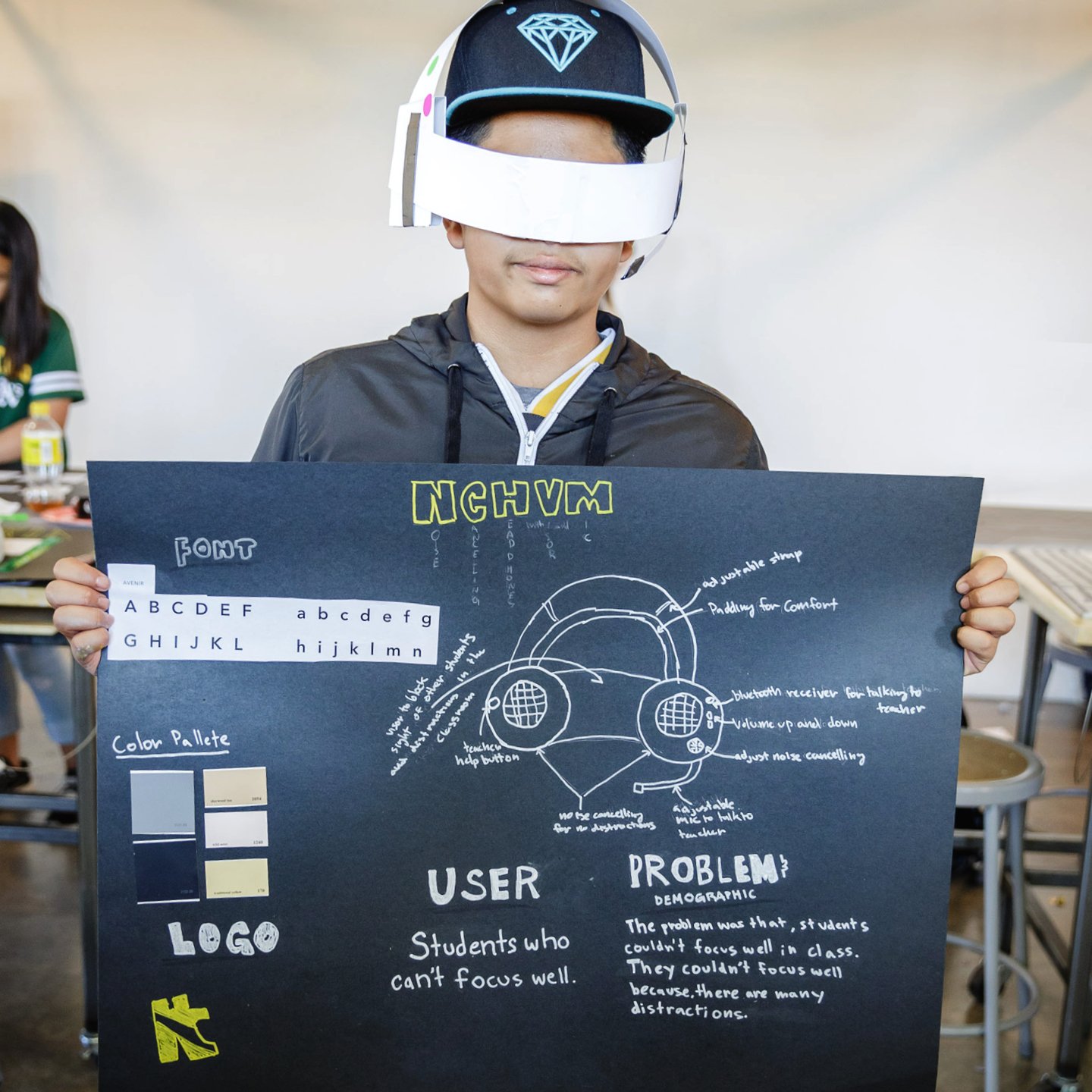

A project developed during an Inneract Project Youth Design Academy held in Oakland. The student was later accepted to Parsons School of Design.

Q: Does design imply the idea of objects that are necessarily useful?

A: Design implies that a process has been taken to come up with a certain solution, but it doesn’t imply that the product is useful. In my role, I get to create something for a lot of people. That’s why it’s a privilege to be a designer. You’re creating for millions and millions of people, or thousands of people. And people get to tell you that what you’re doing is right or wrong, and then you have the chance, if it’s wrong, to make it right and make it better. That’s what we do as designers, and that’s a privilege.

Q: Is design able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

A: If you’re using it solely for pleasure, just call it art. And there’s nothing wrong with that. Designing solely for pleasure negates the whole purpose of design, because design is not for an individual—it’s for people. In that activity, you have to be very intentional about the things that you design for someone or for multiple people that have perspectives different than yourself.

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: Function is a core outcome. I think it’s better to design something that is functional and has a terrible looking form, versus something that has absolutely beautiful form, but nobody can really use it. Function has to come first. And then from function, the holy grail is building something that’s functional and beautiful.

A student working on exercises during an Inneract Project Youth Design Academy in Oakland.

Q: Can a computer substitute for the designer?

A: Ten years ago, I would have had a totally different answer. Now, I don’t know. We’re getting to the point where design can be heavily influenced by the technology that we have at our disposal. Our job as designers is to figure out how to utilize these technologies responsibly and make these technologies accessible for people to use them for the best possible means—and to help them in their daily lives.

There is currently bias in AI, but that will get better. It’s going to evolve. Yet there is a certain human level that technology can never really get to. For example, I’m bringing in my perspective, which connects back to the influence of context in our daily lives. All the things that I’ve experienced and seen in my lifetime shape how I answer a question, versus AI, which is basically a machine responding to a collection of data. AI doesn’t have the perspective of love and understanding and empathy that I might have because I experienced something 20 years ago that changed my life. And that’s where I think the line is drawn between humans and computers.

Q: Does design imply industrial manufacture?

A: Design is just a method. Design doesn’t need technology—technology needs design. People say technology is everything that we use. But I can be in a Sub-Saharan desert in the deep parts of Africa, and design could be pulling branches off of a tree and then making mud and patching leaves together to build and construct a home. I can use the means and things around me. I don’t necessarily need to have my phone or a piece of aluminum. The industrial side is an important side of it, but at the core, design does not need that. Design is a method that we use, and we can use anything at our disposal.

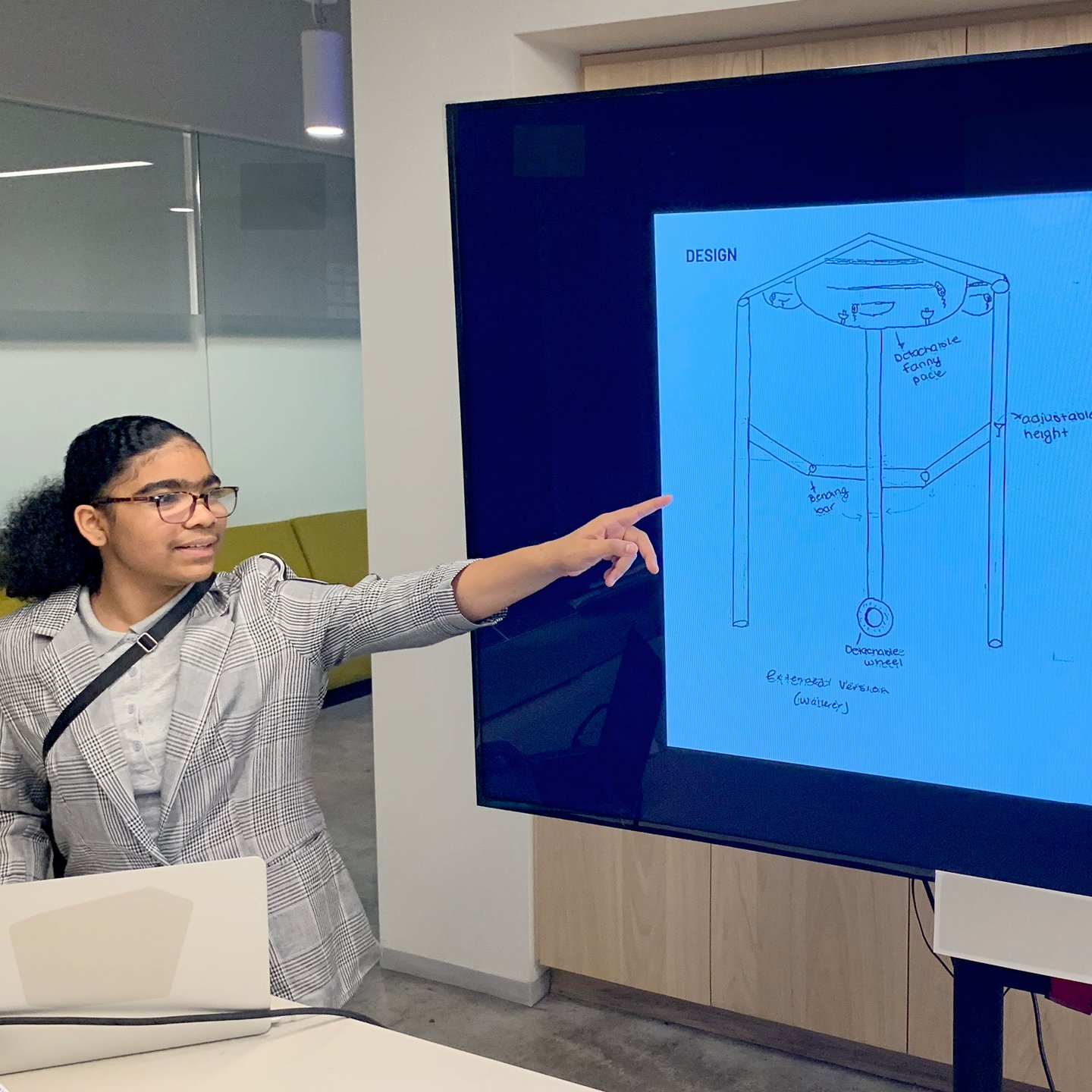

This student created a walker-cane hybrid to support the mobility of her grandmother, seated next to her.

Q: Is design used to modify an old object through new techniques?

A: Yes. Design doesn’t necessarily need to be new and innovative. Sometimes it’s as simple as taking something that’s already been created and making it better.

Q: Is design an element of industrial policy?

A: Design can be and is a part of it. Design is a critical component to making a good product. Ultimately it’s a process that needs to be involved in any facet of production that results in making or creating a product. The deeper questions are, “What leads to good design?” and “What is good design?” That’s where the debate becomes more interesting and also more difficult to articulate.

Q: Does the creation of design admit constraint, and if so, what constraints?

A: The constraints are always a part of the process. Constraints define how you focus and solve a problem. The projects that I’ve worked on that have been the most successful have always had constraints.

Being inclusive and thinking beyond your own personal gains and thoughts is for me what it means to be a good citizen of design.

Maurice Woods

Founder and Executive Director

Inneract Project

Q: Does design obey laws?

A: I hope not. But most times it does, because design is leveraging constraint. That constraint can be not only in the process of design, but can also come from the client. Yet I also feel that design warrants experimentation. I find it very hard to be innovative without experimentation and without breaking some rules eventually, even if you break the rules and then you come back.

Sometimes you have to be bound by the “rules” because they have so many implications for people who are using the product—so you can’t break them. And then there are other times where there’s a process that’s been in place for a very long time and you need to do things differently. I’ve always been more energized by rule breaking. But what I learned and what I always tell my mentees is that you can’t start there. You have to understand the rules first and be very good at following the rules before you can break them.

Q: Should design tend toward the ephemeral or toward permanence?

A: I don’t believe in permanence. I think all things evolve and change. You have certain things that last for a very, very long time, and I wouldn’t speak against that. I just think that it’s innate in humanity for things to evolve and change. I don’t think we should ever be striving to design for permanence. We should be striving for evolving things. To think that we can design something that will be around forever—it’s hard for me to grok and understand that.

Students at an Inneract Project designathon, during which participants visited design firms for a day—here, the San Francisco office of COLLINS.

Q: To whom does design address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

A: Design affects all these groups differently yet it addresses itself to all of them because design is embedded in our lifestyles. People respond based on their level of exposure to design and their understanding that somebody designed this specifically for them. The appreciation doesn’t come from someone saying, “This is design.” Ultimately, you don’t really take note of good design, because it’s intuitive. Yet you generally notice bad design more when you encounter it.

People have their own way of interacting and understanding what good design is, which relates to cultural context. From that lens, diversity in design is crucial. Without a diverse perspective, it’s challenging to create designs that are authentic and cater to everyone’s needs. People with different backgrounds and experiences bring valuable insights. And Black and brown communities, who have unique experiences, deserve representation in the design process to ensure that products are mindful of their identities and values. Too often, we’re being serviced, but we’re not a part of that process for the things that are being designed for us.

Students exploring design projects during an Inneract Project Youth Design Academy, this one held in San Francisco.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises while practicing the profession of design?

A: It comes with the job. And I think the compromises are not always what people think they are. In tech, the compromises that I encounter relate to whether or not things that we want to design for people can be built. Everybody on the team might want to create a certain experience. We want this to be best for everybody, but we don’t actually have the time, the manpower, or even the knowledge to actually build the right thing. So we have to make revisions to the original plan and go with a secondary solution. And that sometimes leads to products or services that don’t always resonate with people.

Q: What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of design and for its propagation?

A: Empathy. Throughout my whole career, that’s always been the primary condition that I utilize the most in delivering a solution to anyone. From the beginning of the process to the manifestation of that idea, my process always centers around, 1) “Am I thinking about the person I’m designing for?” 2) “How is this creation impacting this person?” And 3), “In the long term, is this the best solution, or is this a short-term solution for a bigger problem?” All of that is centralized around empathy and deeply understanding people—who they are, and where they come from.

Students work on projects, guided by an Inneract mentor, during an Inneract Project Youth Design Academy held in San Francisco.

Q: What is the future of design?

A: To me, the future of design is somewhat uncertain. I can’t predict if design is going to be created by people. Perhaps, the future of design could involve people who are driving the systems that design things—a different way of thinking about design.

As design continues evolving, the key question becomes, “How do we utilize this technology in a way where it can create something better?” ❤

Marissa Leshnov is a Black and Russian American photographer based in Oakland, California, whose work explores the complexity of intersectional identity and belonging in the American West.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.