Legacy Portraits: Sam Passalacqua

Spanning more than two decades, Sam Passalacqua’s career at the Eames Office reveals the steady craft, care, and commitment behind some of the studio’s most enduring work.

Eames Office staff members. Front row (left to right): Hap Johnson, Jeannine Oppewall, Sam Passalacqua, Randall Walker. Back row (left to right): Johnny Johnson (Herman Miller), Name Unknown, Alex Funke, Richard Donges, Michael Ripps, Bill Tondreau. Photograph: Robert Staples, 1973.

The Institute is often asked questions such as “What was it like to work at the Eames Office?” “How many staff members did the Office have?” And “What came of those who worked there?” To start our series on the people who helped shape the Eames Office, and by extension the Eames legacy, we begin with someone who spent more time working on the design team than anyone except Ray and Charles themselves: Salvatore “Sam” Passalacqua.

Sam joined the Eames Office in April 1967 on what was supposed to be a three-month trial. Instead, it turned into a twenty‑two‑year run that lasted through the deaths of both Charles (1978) and Ray (1988), ending only with the closure of the Eames Office at 901 Washington in 1989.

Sam didn’t seek attention, but his steady hand and practical skill made him central to how the place functioned. He could take a loose idea and build it into something real—whether that meant creating drawings in the shop, working through stubborn mechanical problems, or the quiet work of keeping projects on track.

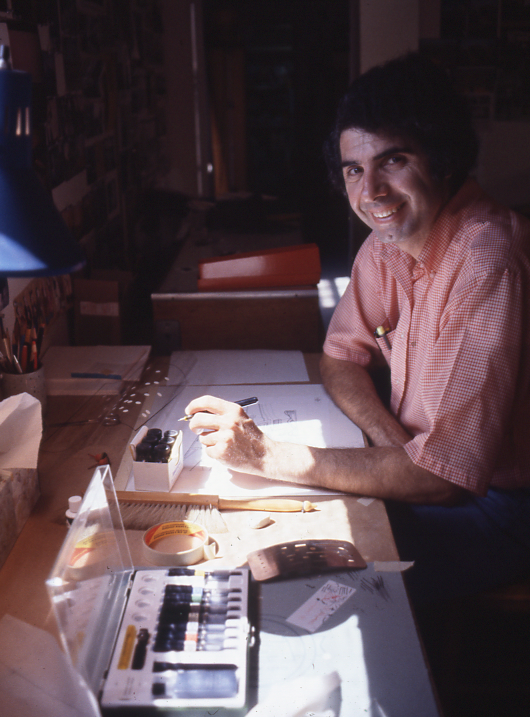

Sam Passalacqua drawing maps for the book Venice, California, 1904–1930, designed by Annette Del Zoppo. Photographs: Annette Del Zoppo.

Sam was born in Sicily on April 21, 1938, and immigrated to Rochester, New York, at three months old with his parents, Diega Antonia Bellomo Passalacqua and Salvatore Eduardo Passalacqua. Sam’s father made his living designing and constructing traditional wooden furniture for the Hayden Furniture Company, often working out of the family’s basement. This gave Sam an early education in woodworking practices that proved invaluable in his future work and which he later credited for his meticulous standards.

In 1950, when Sam was twelve, he moved to Los Angeles with his mother and younger brother, Gerald, to join relatives. While they waited for his father to follow after wrapping up life in Rochester, tragedy struck: Salvatore Sr. died of a heart attack while beginning his train journey west. The family stayed in California, close to their extended network.

Sam grew up in Los Angeles. He studied at both the Los Angeles Trade-Technical College and California State University, before enrolling in the industrial design program at the University of Southern California.

Sam graduated from USC in 1966. To help pay for school, he worked nights as a bank messenger, and he kept that job even after graduating. He married Janet Rauh in 1962; the two later divorced in the early 1970s.

Sam’s entry into the Eames Office came through the mentorship of a USC professor named Sal Merendino, who was determined to get Sam started in design. Merendino drove him to the Eames Office, sat with him through the interview, and—by family accounts—did most of the talking. The offer was $2.50 an hour for a three‑month probationary period. Sam, thinking about supporting his young family, hesitated. Merendino insisted he take it. The probation became a career.

Eames Teak and Leather Sofa, the last piece of new furniture design produced at 901 Washington. Artifact# 2023.591

At the Office, Sam arrived at a time when much of the work for Herman Miller involved improving older designs and introducing new products. He began with production drawings in the shop, contributing to work on the Eames Universal Base and detailing for the Intermediate Desk Chair. He was especially proud of a caster concept he worked on for the chair bases, a design that was also used for the Eames Drafting Chairs.

Over the years, Sam worked on nearly every major furniture program: the Loose Cushion Group, the Soft Pad Group, the Chaise, the Secretary Chair, the Drafting Chair, and the last new furniture design to come out of the Eames Office, the Teak and Leather Sofa.

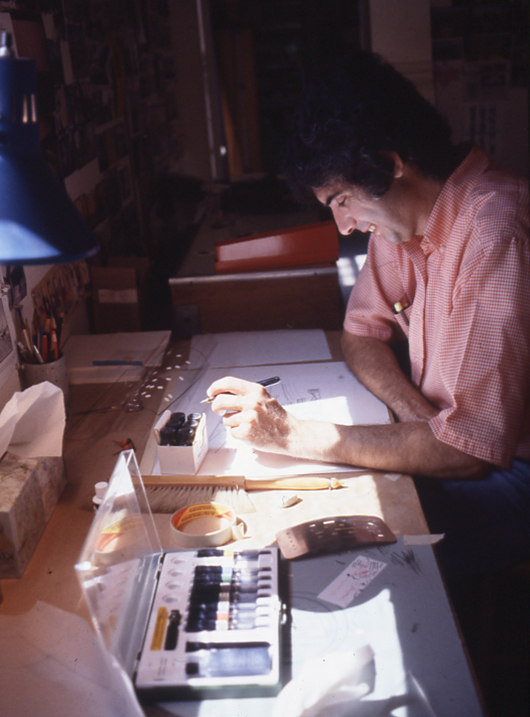

Left: Shooting footage of aquatic life in the fish tanks at Eames Office to better understand marine habitats for the National Aquarium Proposal. Artifact# A.2019.2.3975.003

Right: Model of the National Aquarium. Artifact # A.2024.099

His work wasn’t limited to furniture. In 1968, he revived and expanded the marine animal tanks used in the Eames Office’s research for the National Aquarium project. He learned how to keep delicate marine life healthy and stable, working through trial, reading, and conversations with biologists. Some of his observations were published in a paper titled “Algae Removal by Hermit Crabs” in the journal Drum and Croaker in 1970.

Karl Rimer, who worked alongside Sam at the Eames Office for five years, remembered how seriously he took the aquariums. Sam kept his desk close to the tanks so he could keep a constant watch, making sure the fish were safe and healthy. One fish in the largest aquarium—nearly four feet high—kept jumping out. It survived more than once, but after the second escape, Sam built a simple, fish-friendly cage over the top of the tank.

Rimer also remembered that Charles trusted Sam with the patent drawings—work that had to be exact, with no room for sloppiness. It was another kind of caretaking: technical, and precise.

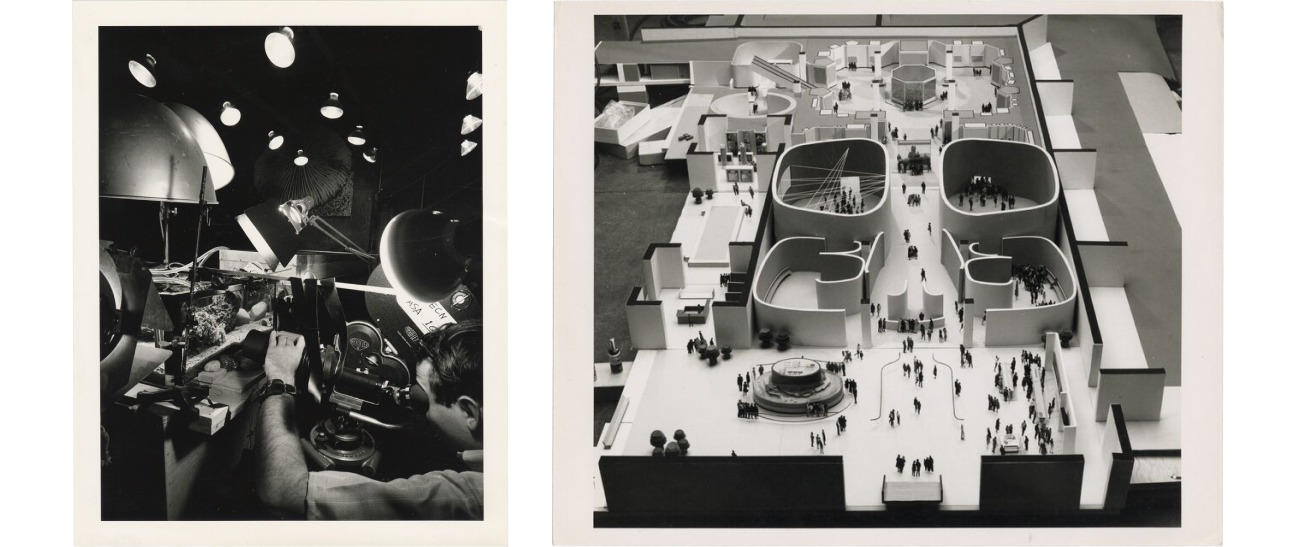

Sam also played an important role in the Office’s large science exhibitions for IBM. He managed mechanical systems for the traveling shows, including the rotating calendar drum for Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond and The World of Franklin & Jefferson bicentennial exhibition in 1976. When Charles publicly singled out Sam’s work on the IBM projects as exceptional, it became one of the proudest moments of Sam’s career.

Brochure for Mathematica: A World of Numbers and Beyond. Artifact# A.2019.2.1812

Over time, Sam’s dedication extended well beyond projects and production. During Ray’s widowhood, Sam became her daily support. He helped manage the building, kept the work moving, and stood by her through illness and uncertainty. Their relationship was shaped by respect and by a shared commitment to preserving the work.

After the Eames Office closed in 1989, Sam kept continuously busy with restoration and hands‑on work—repairing furniture, selling memorabilia at the swap meet, and taking on various architecture projects. He also became the caretaker for his mother until her death in 2004.

Sam was an obsessive collector. He collected real estate, Coca‑Cola, Budweiser, and Olympic memorabilia and historic posters. On weekends, he often took his daughters with him to the Rose Bowl Flea Market, where he sold items from his memorabilia collections. But most important to him were Eames items—purchased from or gifted by Charles and Ray, as they were known to do with employees—none of which he ever sold. Those he saved, believing they belonged in a future Eames museum. He even laid out that vision in a multi‑page, handwritten letter to Ray and Charles’s daughter, Lucia Eames, which she prized.

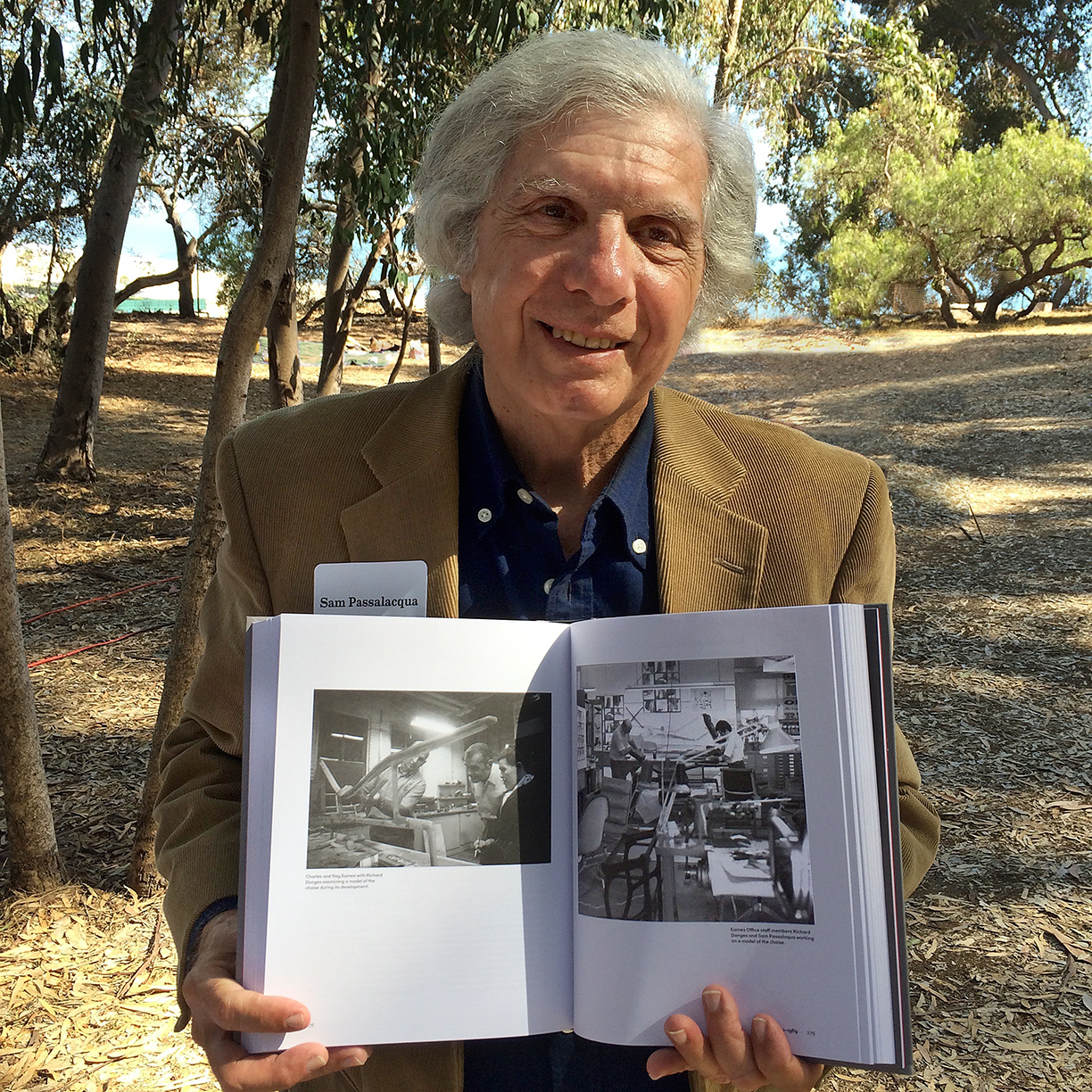

Sam Passalacqua standing in the meadow at the Eames house, holding a copy of An Eames Anthology. Photograph: Daniel Ostroff, 2015.

Just as family mattered to Ray, Charles, and Lucia, family mattered deeply to Sam. He was the father of three daughters—Annette, Renee, and Michelle—and was granted full custody of them in 1974, at a time when that was far less common for fathers. He took that responsibility seriously, while occasionally struggling as a single working parent.

He also had a deep affection for animals, adopting more than twenty dogs, along with orphaned cats and even a turtle, over the years. And he was an enthusiastic photographer, often the one behind the camera at family events and performances, steadily building a record of family life one picture at a time.

Sam passed away at age 82 on January 17, 2021, survived by his daughters, their children, and his many cousins back in Sicily. Ray and Charles’s grandson Eames Demetrios offered a eulogy and served as a pallbearer.

Sam Passalacqua is remembered not only for his craft, but also for the way he worked: carefully, consistently, and focused on doing the job well. In that sense, he carried forward a basic Eames principle—make it right, and make it last. Few were more selfless stewards, or more deeply committed to advancing and safeguarding the Eames legacy, than Sam. ❤

Stay tuned for our next installment in this series Legacy Portraits.

—Daniel Ostroff is the Chief Scholar of the Eames Institute and the editor of An Eames Anthology (Yale University Press). Ostroff was a consultant to the Eames Office from 2006 to 2025, and has been an advisor to Herman Miller, Vitra, and museums globally.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.