Design Q&A: Kelli Anderson

By asking unanswerable questions, following the trail of curiosity, and doing things “wrong,” designer Kelli Anderson invites us into a world where wonder abounds.

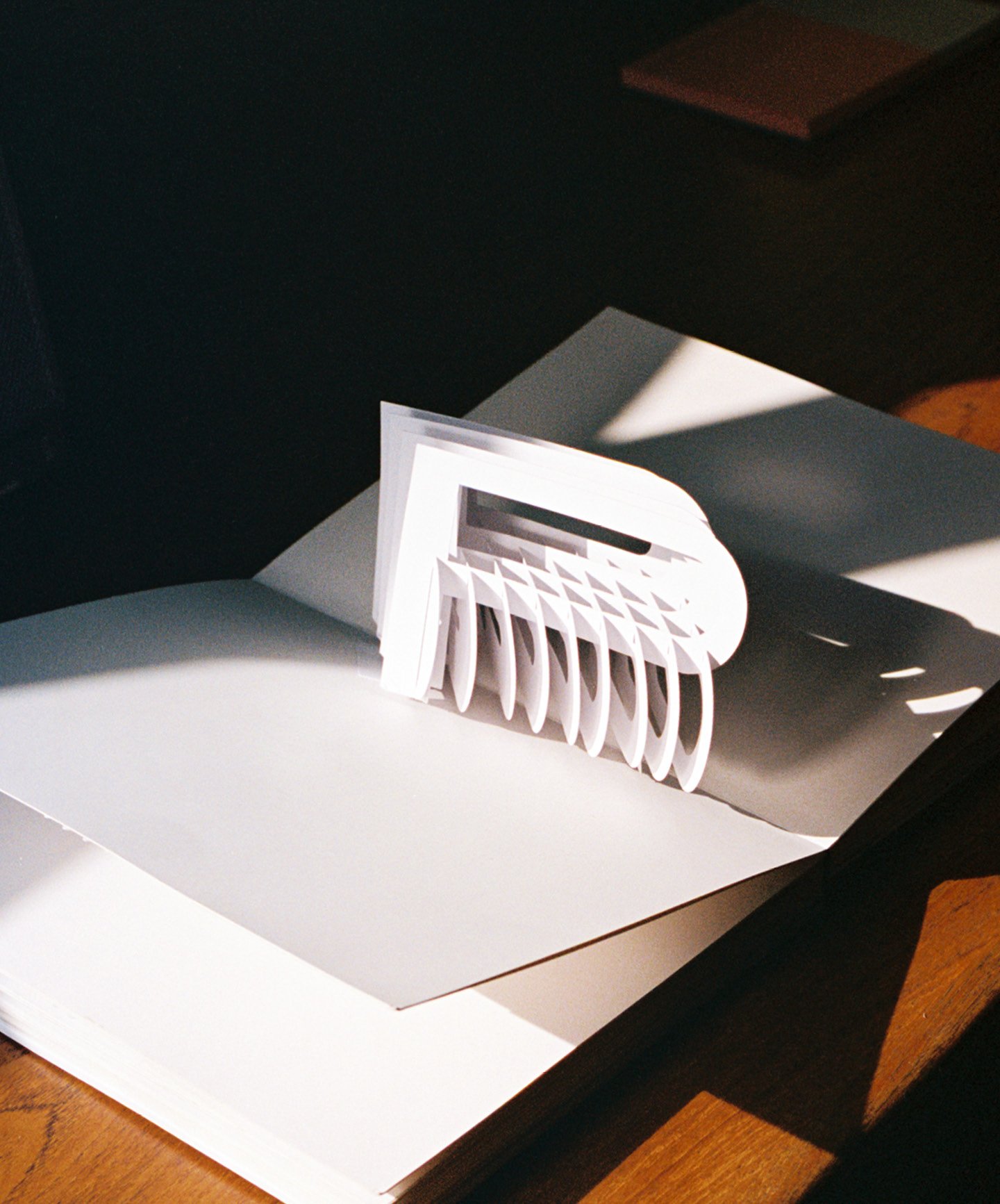

Kelli Anderson at work in her Brooklyn-based studio on her latest project, Alphabet in Motion: How Letters Get Their Shape.

In designer Kelli Anderson’s world, things both are and aren’t what they seem. A book pops up to become a camera, a paper wedding invitation functions as a record player, and a risograph becomes a lo-fi tool for animation. She delights in making everyday objects misbehave—or at least behave in ways we don’t expect. “I’m always trying to do things just a little bit wrong,” she says. But what she’s actually doing is designing wonder.

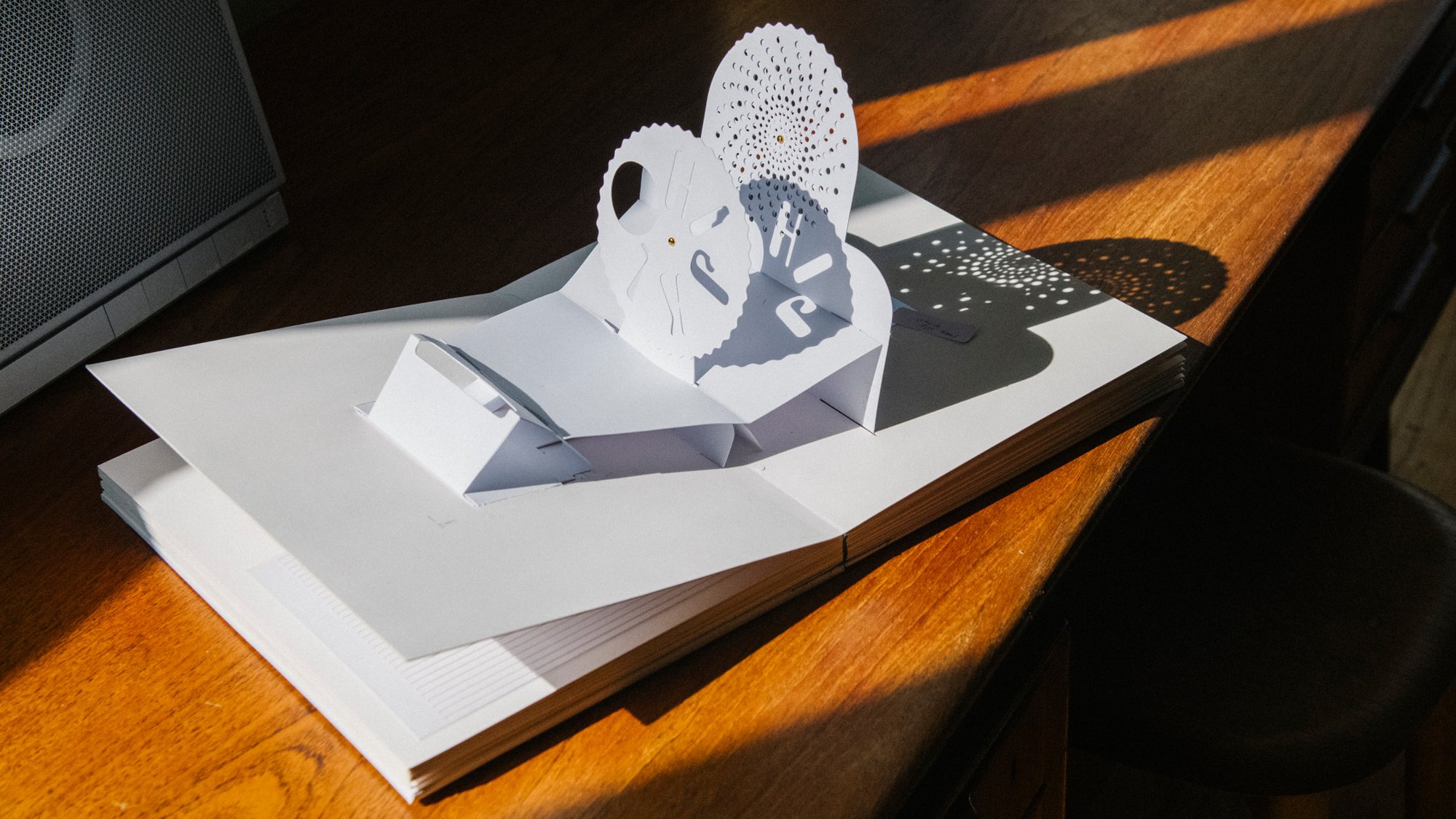

Anderson’s work is often a mixture of fine art and physics: a manifesto and cut-out portal for Herman Miller’s Ideas magazine that reflects on the transportative power of design; a flipbook that remakes Ray and Charles Eames’s Powers of Ten film using photographs found via Google Images search to prove the scale of the Internet; and This Book Is a Planetarium, a pop-up book that features fully functional paper gadgets like a speaker, a perpetual calendar, and a musical instrument inside. She uses the phrase “paper engineering” to describe how she explores the physical, acoustical, and functional properties of the material.

Born in New Orleans, Anderson earned a BFA in studio art from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette and then two degrees—a masters of studio art and a masters in the history and theory of art, design, and architecture—from Pratt Institute. After graduate school, she worked in a digital design studio, but, feeling out of place, quit after a few months to take a job archiving glass-plate negatives at the Museum of Natural History. Meanwhile, she had become the go-to whenever her friends needed flyers or posters for their creative pursuits. Eventually, graphic design became her profession. Her outsider perspective is part of the reason why her work is so electric.

“Because I didn’t go to school for graphic design and I wasn’t told there’s a certain way to do this and a certain way not to do it, I approached graphic design more like a fine artist or in this more conceptual, experimental way,” she says. “I’m always worried I’m kind of embarrassing myself, but it’s worked out so far.”

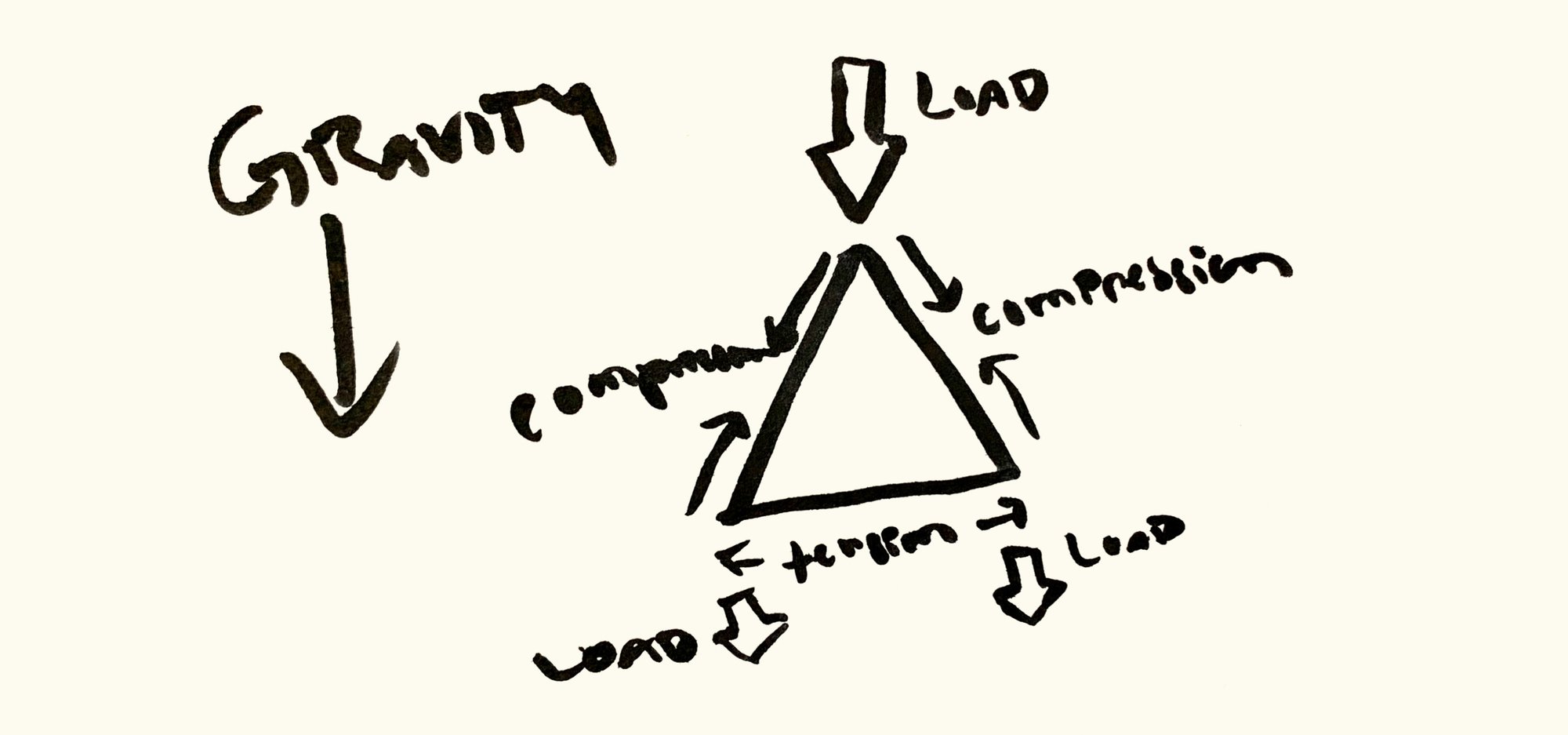

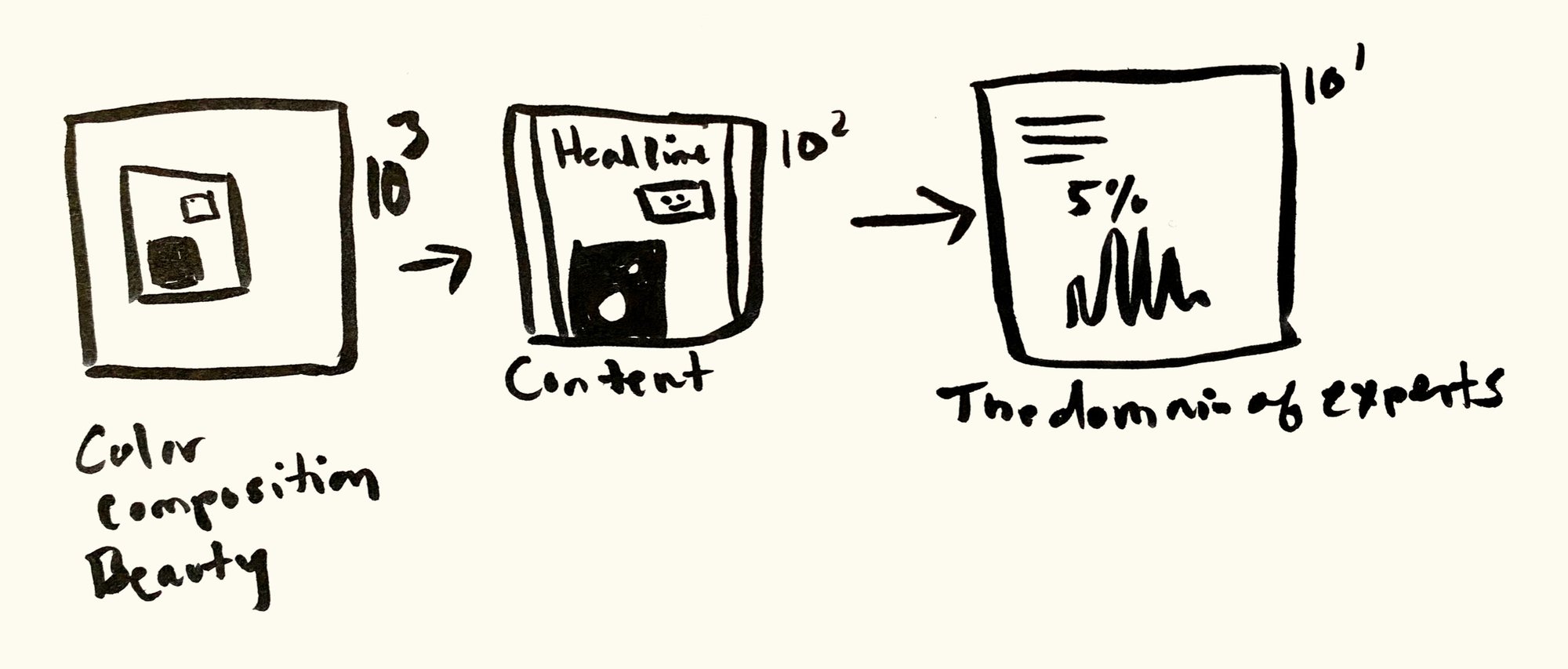

While Anderson is a maker of many things, creating books is her current obsession. “There’s a parallel mechanism of increasing, stepped granularity between how curiosity works and how design works in terms of getting people into a topic. Those two things converge in the structure of a book,” she says. “You see the book from across the room and its colors and shapes are appealing enough to lure you a little bit closer to start reading the large text, then if that is interesting enough, you’re pulled into the weeds of the smaller text. The dual mechanisms of design pleasure and the pleasure of following your own curiosity can be paced—doled out like a breadcrumb trail leading deeper into a topic.”

Her latest project is Alphabet in Motion: How Letters Get Their Shape, a pop-up book that explores the history of letterform design, which offered increasingly deeper layers of insight for Anderson, though she had studied the topic briefly in school and casually researched it for years. Wading into the unknown, like a scientist might explore a new realm or hypothesis, is a theme across much of her work. She conveys that she herself is figuring out the world and inviting us into her sense of discovery.

“When there’s an active question and something that you’re unsure about, there’s just a lot more vitality in it than something you’re already certain about,” Anderson says. “If the work I do is an experiment, meaning it could either be a massive failure or a great success, I’m much more likely to do that than something that will definitely work. It’s not a good business strategy, but it’s a good strategy for keeping yourself moving forward.”

Alphabet in Motion’s distributor sent the final order for the book to the printer in early February, following a fall 2024 Kickstarter campaign that raised $268,631 to fund the project, significantly topping Anderson’s goal to raise $50,000. In between shepherding current projects and plotting future experiments, she remains actively involved in mentoring visual artists and designers while teaching three classes every fall semester, including an NYU class on risograph animation and a Cooper Union course on the art of the book. She’s proud that techniques she developed are mainstreaming, but that’s making her a little restless, she says. “It’s this feeling of Oh, I’ve got to push the envelope farther.”

In the 1972 film Design Q&A, French curator Madame Amic presents Charles Eames with a series of archetypal questions about design’s meaning and purpose. As part of an ongoing feature in Kazam!, we posed those same questions to Kelli Anderson.

Q: What is your definition of design?

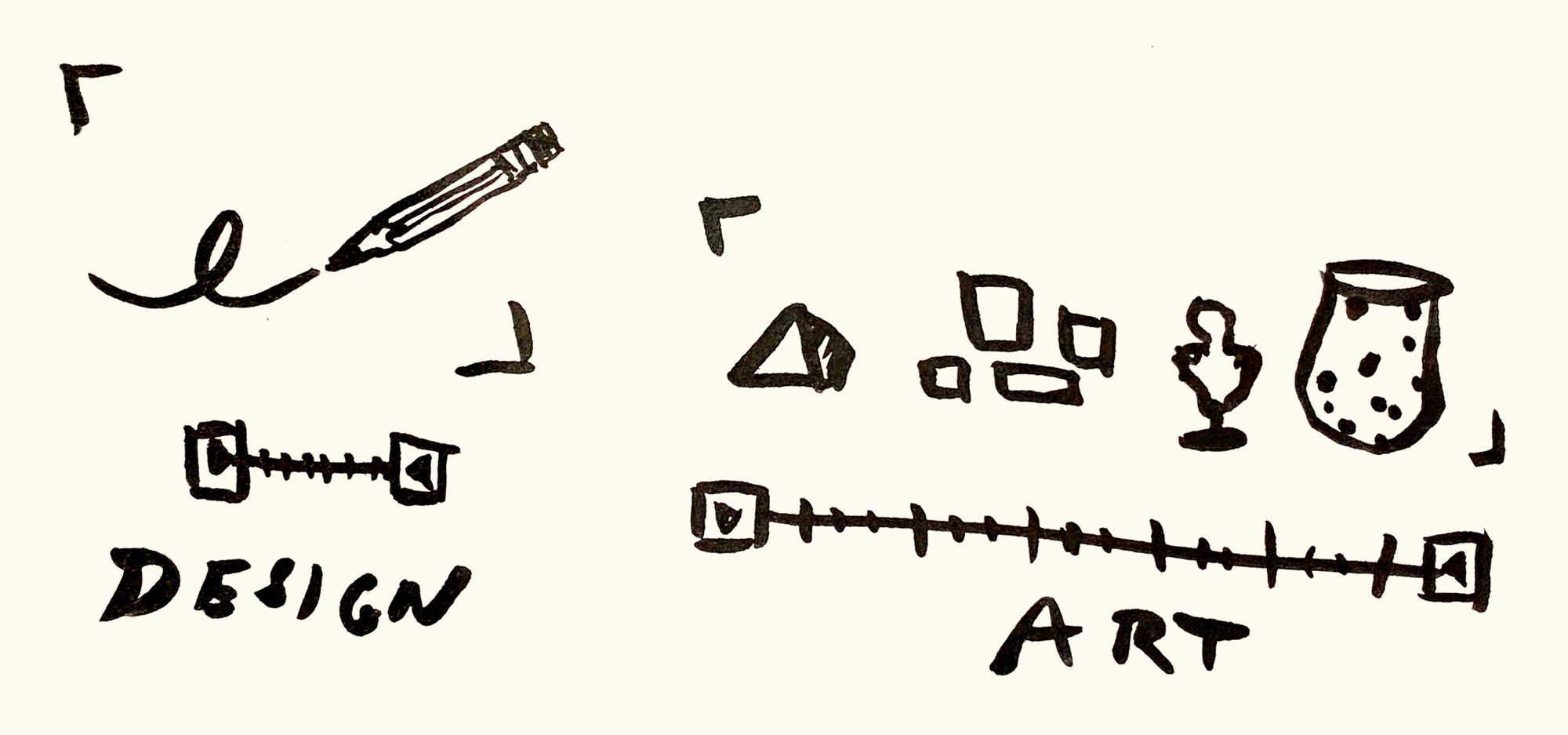

Q: Is design an expression of art?

A: Both design and art can be equally conceptual, philosophical, experimental. What separates design from art is the scale of the context of the problem. Design problems seek grounding in specificity. In designing a pencil, one would usually think a lot about both the human hand and the material affordances of graphite. In making art, you’re interacting with more of an infinite scale of context.

Q: What are the boundaries of design?

A: There are no predefined boundaries. The activity of the designer is to hone in on them.

Q: Is design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

A: Zones of the environment do not dictate its edges. Instead, zones of human experience do.

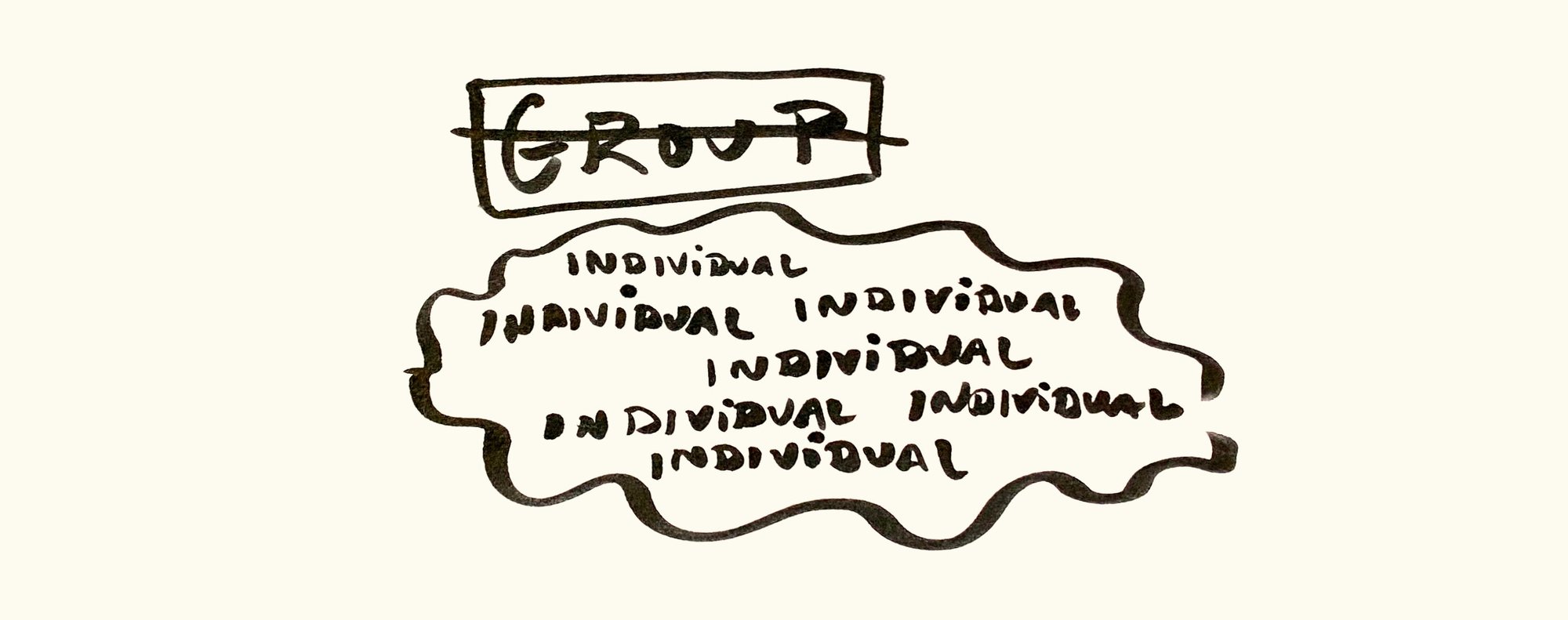

Q: Is design a creation of an individual or a group?

A: The notion of firsthand is crucial to both making and experiencing design. A “group” is one layer of abstraction above entities that are capable of participating in the world firsthand. A collection of individuals can certainly negotiate design decisions. But “design by committee” happens when the firsthand is ignored.

Q: Is there a design ethic?

A: I think design ethics and humanist ethics are one in the same. Pursuing awe is one that I practice.

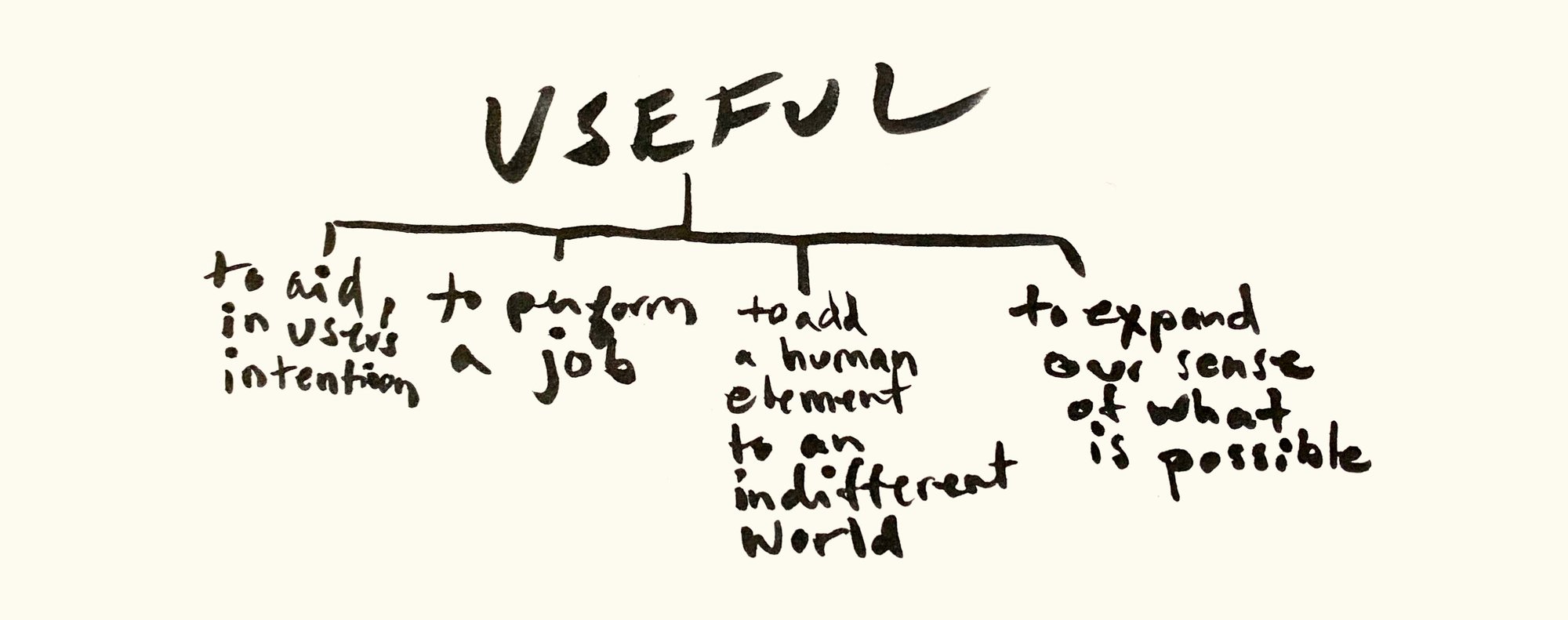

Q: Does design imply the idea of objects that are necessarily useful?

A: Sure, if your definition is capacious.

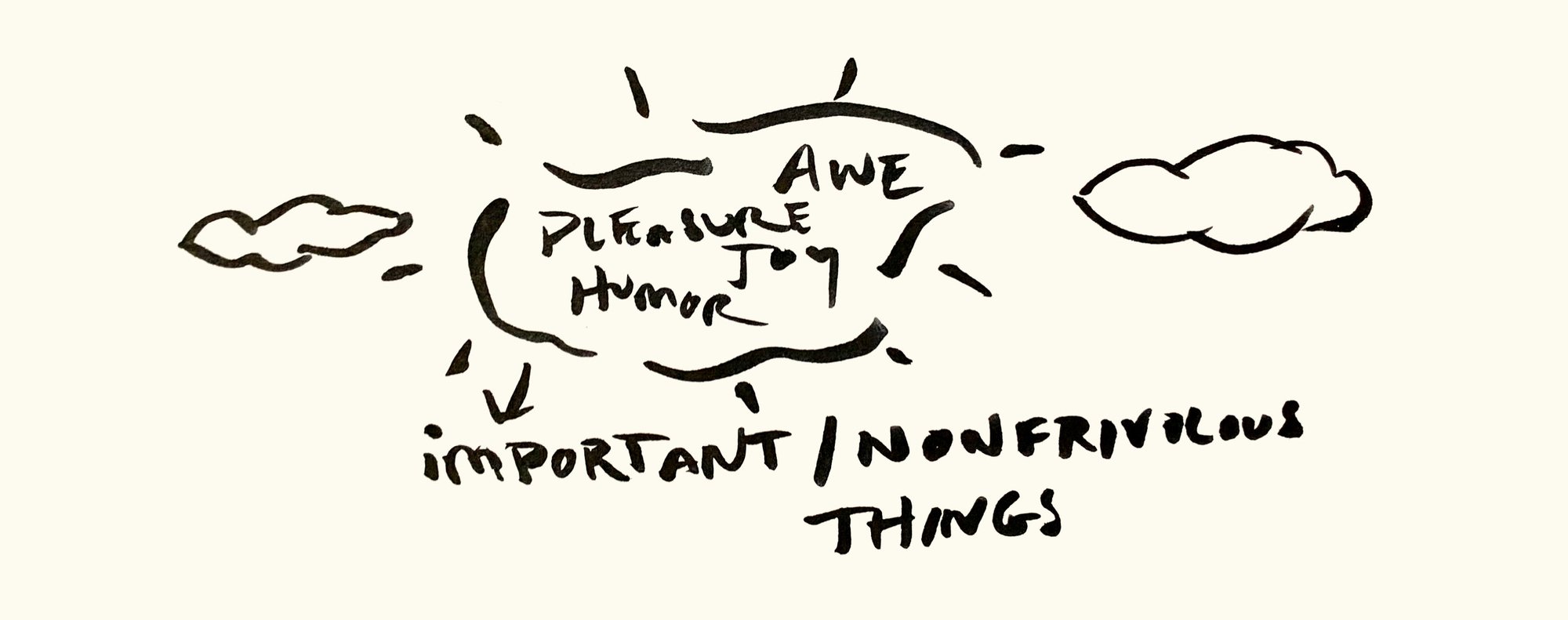

Q: Is it able to cooperate in the creation of works reserved solely for pleasure?

A: Yes. Pleasure is as important and useful to us as sunshine and oxygen. Design knows this.

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: It’s certainly a very good place to start.

Q: Can the computer substitute for the designer?

A: I’m usually not fooled.

Q: Does design imply industrial manufacture?

A: As long as a human hand is behind it, the exact tool or process does not matter much.

Q: Is design used to modify an old object through new techniques?

A: Of course! This is of increasing importance as we live on a planet with limited resources.

Pleasure is as important and useful to us as sunshine and oxygen. Design knows this.

Kelli Anderson

Designer

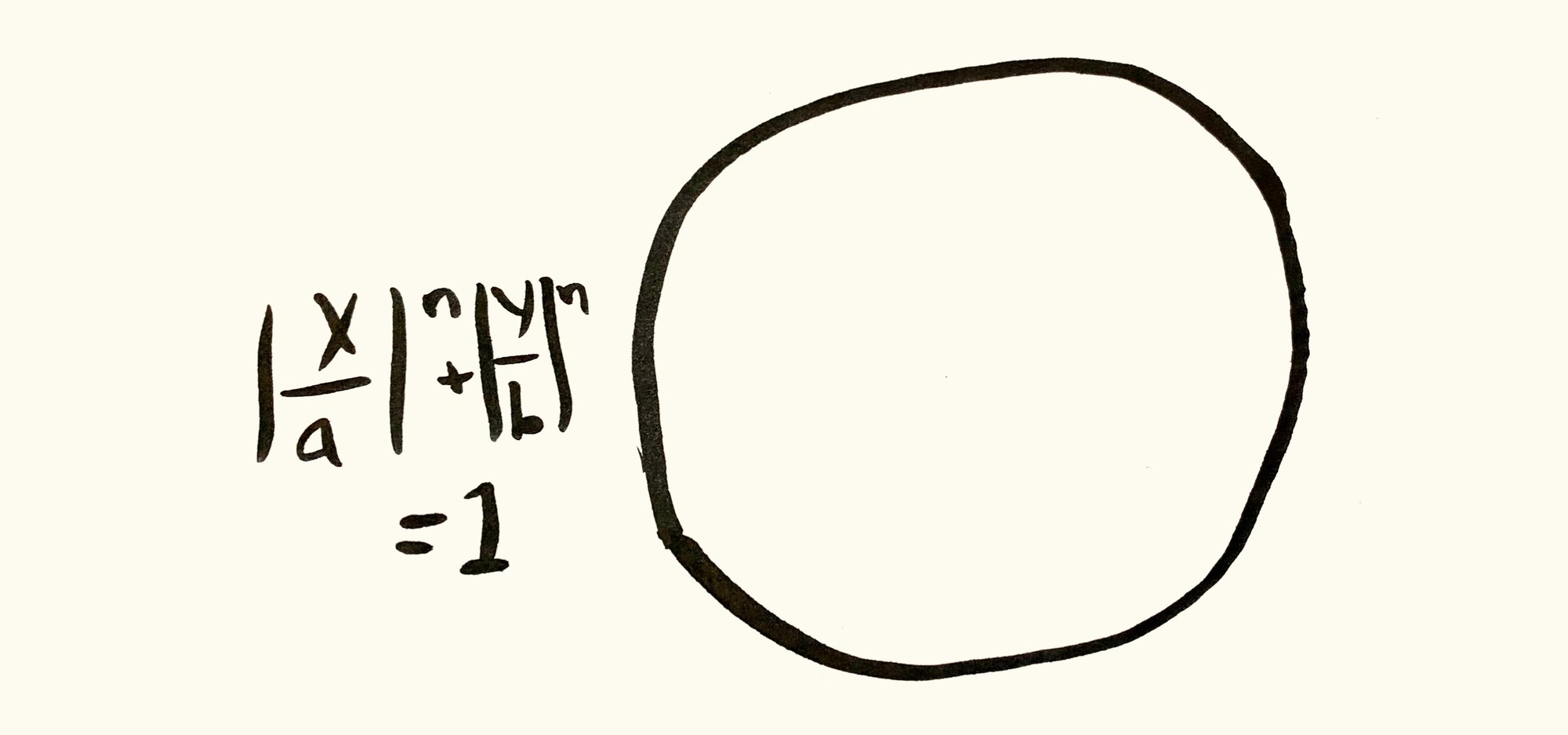

Q: Is design an element of industrial policy?

A: Sure! I’m thinking of how Piet Hein’s super ellipse made it into Stockholm’s civic planning (through roundabouts, etc.) and into industrial design in the form of plates, tables, and television screens in the early ’60s. It did so by dint of being just the right shape at just the right time!

Q: Does the creation of design admit constraint, and if so, what constraints?

A: The only important constraint is that we cannot control how the end user interacts with our design. (Things like “hostile design” = a crime against design.)

Q: Does design obey laws?

A: A few of them are important.

Q: Ought design tend toward the ephemeral or toward permanence?

A: There is a place for both.

Q: To whom does design address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

A: Ideally, design whisks the “greatest number” to “enlightenment” by holding-up* under successively granular levels of scrutiny.

*i.e., being visually captivating, well-written/structured, and connecting the user with a truth. Each step brings the audience in a little closer, like leaving a breadcrumb trail.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises while practicing the profession of “design”?

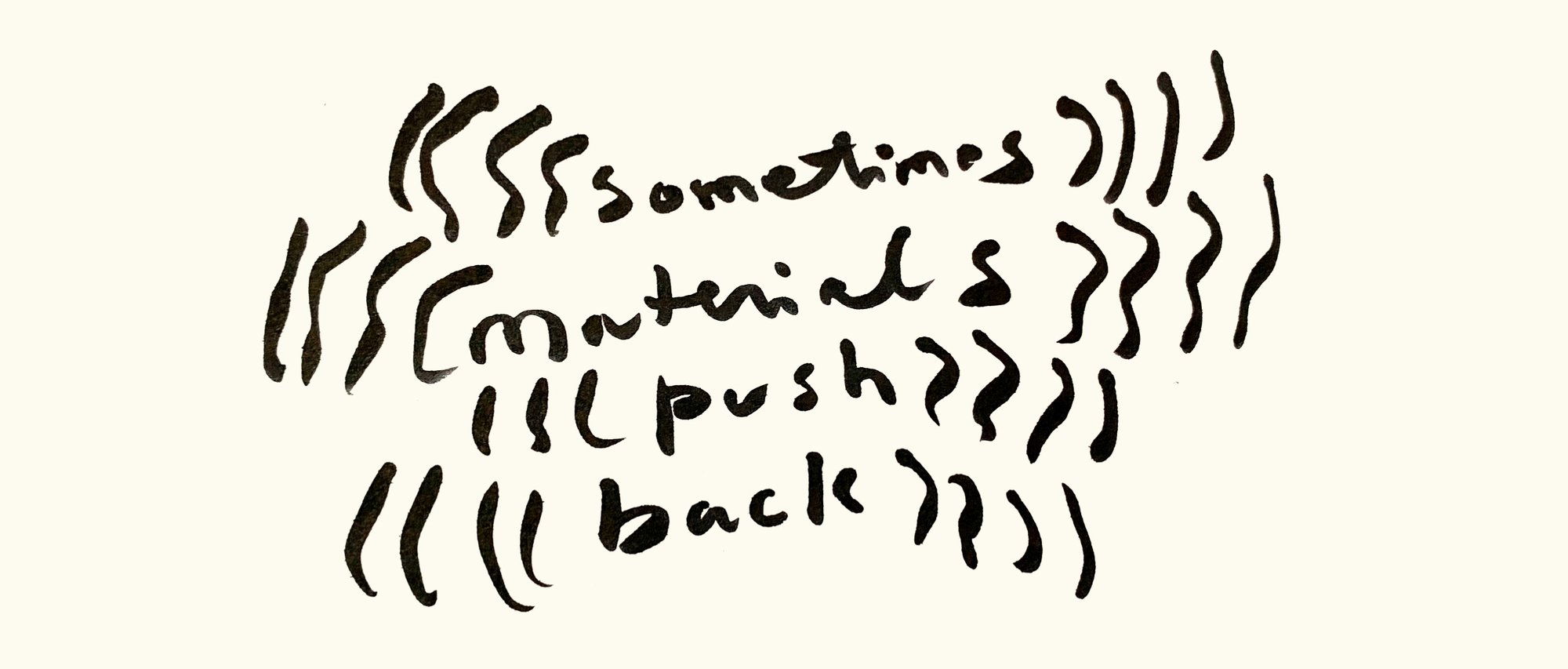

A: Sometimes materials push back.

Q: What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of design and for its propagation?

A: To connect human beings to their world.

Q: What is the future of design?

A: I suspect design’s methods and processes will come to more closely mirror those of natural and biological processes. ❤

Diana Budds is a New York–based design journalist. Her writing has recently appeared in the New York Times, Dwell, Fast Company, and Wallpaper*, among other publications.

Adrianna Glaviano is a photographer who works for clients in the fields of interiors, food, architecture, travel, art and fashion. She is based between New York and Milan.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.