Design Q&A: Shigeru Ban

Shigeru Ban creates architecture where purpose intersects with form. While he says he isn’t an altruist, his work suggests otherwise.

Shigeru Ban photographed at the Tokyo office of Shigeru Ban Architects.

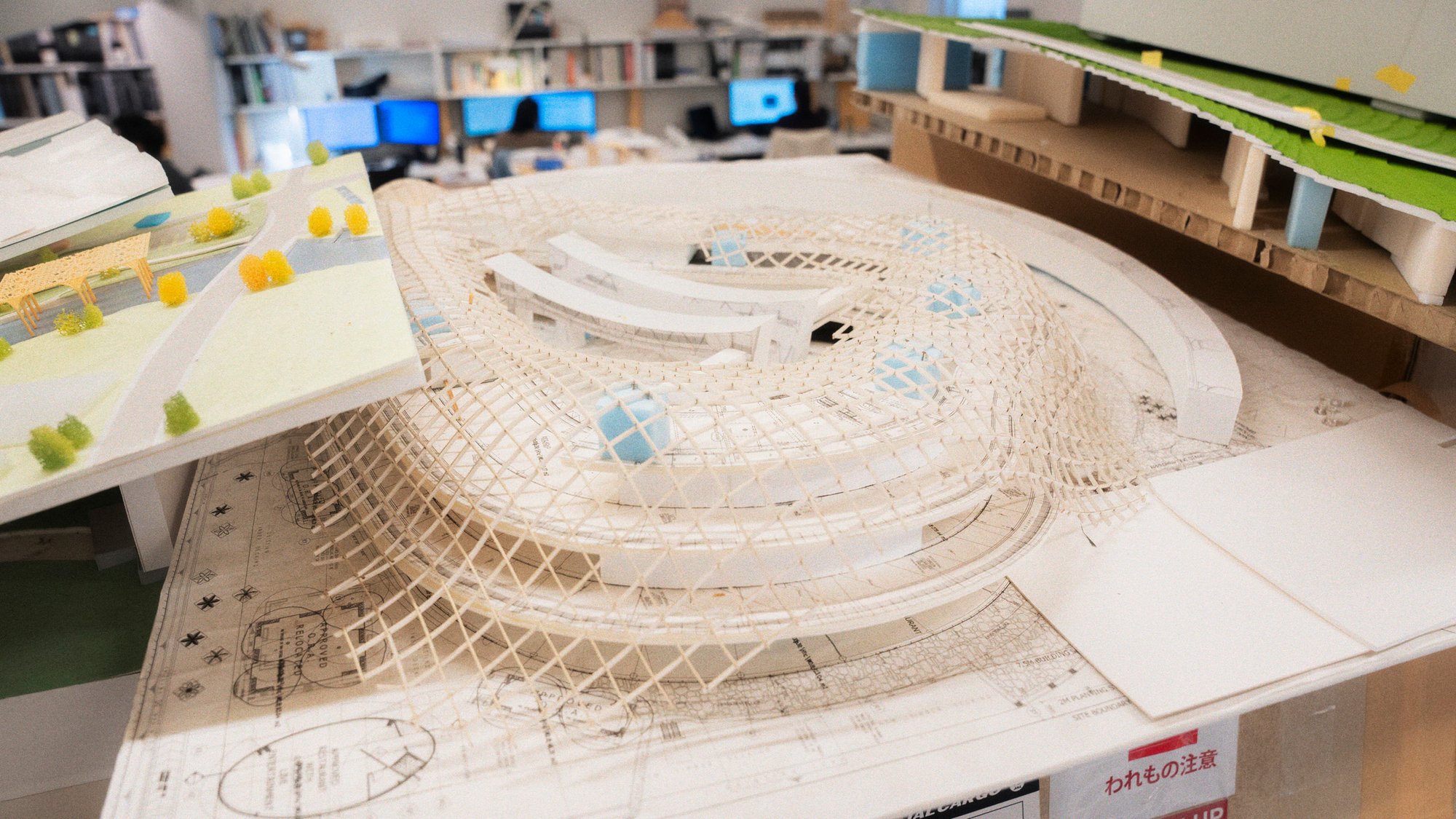

Shigeru Ban’s architecture celebrates geometry in defining an experience of space: In residences including the Sagaponac House and Picture Window House, straight lines, glass walls, and rectangular forms lend an aura of simplicity along with a cinematic frame for experiencing the natural surroundings. For the Aspen Art Museum, completed in 2014, a woven latticed exterior, made of wood and paper, casts grids of shadows onto a grand staircase and behind it, the glass-walled interior. La Seine Musicale, a concert venue in France, features a geodesic-like dome wrapped with a solar panel array that follows the movement of the sun.

While these geometries have a rational component to them, the aesthetics and experience of the buildings go beyond the intellect. These structures have heart; Ban acknowledges that emotion is central to his creative process. “Architecture is just the expression of my life,” says Ban, speaking from his firm’s Tokyo office on an early winter morning. “It’s not really about making buildings, it’s about expressing my feeling. When I visit a site, I feel the potential beauty of the site, or a potential problem. And I just draw what I feel.”

In addition to his projects for cultural institutions, corporate headquarters, and high-end developers, the Pritzker Prize–winning Ban has continually brought this sensitivity to projects for humanitarian interventions, creating temporary structures for people who have lost homes as a result of conflict or natural disaster; in these cases, deep empathy is the driving force behind the design.

In 1995, he first designed temporary structures to provide housing for refugees displaced by the genocide in Rwanda. Over the years since, he has led projects for communities in Turkey, China, India, Japan, and New Zealand, to name a few, and established the nonprofit Voluntary Architects’ Network to coalesce community and support for the mission. True to form, during 2023, Ban traveled to Lahaina, Hawaii, to design and plan a temporary structure for a Buddhist temple that had burned down during the August 2023 wildfires. He had also visited Cairo to discuss with an architecture professor and his students the possibilities for temporary architecture in Gaza, where Israeli forces have leveled vast communities during their siege.

Ban has arguably done more to benefit people in need than any other living architect, yet he is dismissive when asked about his philosophy of altruism in architecture. “It’s nothing special,” he says. “If a medical doctor sees some injured people, they will treat them—whether they are a friend or enemy. So if we as architects see that somebody is suffering with poor living conditions, we have to do something.”

Ban’s humanitarian work has been shaped by another signature that is evident throughout his buildings—his long-term passion for building with materials that are upcycled or that have lower environmental impacts than many contemporary construction materials. In 1986, he first created an exhibition interior using paper tubes, which are made from recycled paper, are recyclable themselves, and are ubiquitously available throughout the world. He continued the application of the tubes in a weekend home he built for himself, in humanitarian housing, and numerous other projects. For many years, Ban has also been creating structures with timber, a material whose aesthetic and environmental properties—highly insulating, and less embodied carbon than steel or concrete, for instance—he has showcased in small-scale residences, cultural venues, and high-rises alike.

Ban resists the effort to be categorized or labeled when, rather, he does what he does for its intrinsic value. “When I started to develop the recycled paper tube structure in the middle of the ’80s, nobody was talking about this,” he says of sustainability, irked by the retroactive association with the trend, “and I started developing this not because of this movement.”

Ban’s upcoming projects include a destination campus and distillery for the brand Kentucky Owl that includes a trio of pyramids made with timber; a high-rise residential tower for a new development in Antwerp; and a pavilion for the World Expo 2025, held in Osaka. That structure uses carbon fiber, which Ban likes for its strength and light weight. The material allowed him to create a pavilion that does not need concrete piles, which would be otherwise necessary on the landfilled terrain where the structure will be located. Ever intent to avoid waste, Ban plans to re-use the pavilion for another project to be determined, and criticizes current practices in expositions: “Many of the buildings are just a competition of unusual shapes without thinking what to do with the material, how to demolish, and so on, afterwards.”

Looking toward the future, Ban wants to continue learning, which he compares to the imperative to see disaster areas firsthand so he can figure out how to best serve local needs. “Just like going to the disaster area by myself, it’s part of my training–instead of just sending stuff,” he says. “So I have to train. I have to be trained. I have to learn more, I have to experience more. I don’t know which way exactly, but I like to keep training.”

In the 1972 film Design Q&A, French curator Madame Amic presents Charles Eames with a series of archetypal questions about design’s meaning and purpose. As part of an ongoing feature in Kazam! Magazine, we posed those same questions to Shigeru Ban of Shigeru Ban Architects.

Q: What is your definition of design?

A: It is not possible to describe “architecture” in words. I just want to show my way of life to my students.

Q: Is design an expression of art?

A: It is completely different from “art.”

Q: What are the boundaries of design?

A: The rationalities of each material.

Q: Is design a discipline that concerns itself with only one part of the environment?

A: No, everything has to be considered together. The solution has to be discerned from all the requests, the requirements, the problem, and the wish of the client together—this is not done through solving one by one.

Q: Is design a creation of an individual or a group?

A: My structural design is the expression of my vision only. When I have worked with people such as Hermann Blümer, Gengo Matsui, and Frei Otto, this wasn’t really collaboration. I learned a lot from them. They are my teachers, and I am their apprentice.

Q: Is there a design ethic?

A: I just hate wasting material, time, and energy. When I started developing structures with humble, recycled, reusable material in the middle of the ’80s, no one—including myself—was considering any ecological and environmental problems. I just do not waste anything.

Q: Does design imply the idea of objects that are necessarily useful?

A: I would like to make things useful. But I believe that there are many people who make things that are not useful, and that is natural.

Q: Ought form to derive from the analysis of function?

A: I like the approach of “form finding method.” I do not like the approach of “form making method.”

Q: Can the computer substitute for the designer?

A: Architecture was better when we did not have “high technology” like computers. Great architecture takes time to design and build. In contrast, the computer is a tool to save time. Therefore, it is not necessary to use a computer to make great architecture.

When we draw a structure by computer, it is connected to our brain. When we draw it by hand, it is connected directly to our heart. In this process, we finish little by little what’s more important, then go to the details. Even when the drawing is not completely finished by hand, it’s already understandable what is important. But in the computer drawing, we are just assembling the details without having the harmony, without showing any priority relating to the importance of ideas.

When we draw a structure by computer, it is connected to our brain. When we draw it by hand, it is connected directly to our heart.

Shigeru Ban

Founder

Shigeru Ban Architects

Q: Is design used to modify an old object through new techniques?

A: I do not develop something new or develop new techniques. I just use existing things to find new functions.

Q: Is design an element of industrial policy?

A: I don’t want to be influenced by somebody or a government. I just do whatever I like.

Q: Does the creation of design admit constraint, and if so, what constraints?

A: If there is no constraint, it is not possible for me to design.

Q: Ought design tend toward the ephemeral or toward permanence?

A: Many of my temporary structures made of paper tubes have become permanent. Many commercial buildings in concrete, made by commercial developers, are bought by other developers and destroyed to make new buildings. Therefore even concrete buildings are temporary when they are built to make money.

Q: To whom does design address itself: To the greatest number? To the specialists or the enlightened amateur? To a privileged social class?

A: Each project is designed according to the client’s program and requests—some are for the great number of people, some are for the specialists, and some are for the privileged. More generally, I am disappointed by my profession of architects, because we mainly work for the privileged. I want to work for the general public and even people who lost their houses because of natural disasters.

Q: Have you been forced to accept compromises while practicing the profession of “design”?

A: I always give up some things to meet a budget so that I can finish a project without changing the main concept. I do not call it a compromise.

Q: What do you feel is the primary condition for the practice of design and for its propagation?

A: When I can share the same idea, concept, and values with a client, I am excited to work on a project with them.

Q: What is the future of design?

A: I do not think the role of architects will change even in the midst of cultural, scientific, and technological developments. ❤

Nobu Arakawa is a Japanese-English bilingual director and cinematographer based in Tokyo, renowned for his visionary approach to storytelling.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.