Scaling a Single Form

The Eames Shell Chair has become one of the most recognizable design icons of the 20th century, but its present-day ubiquity belies its circuitous origins and radical premise.

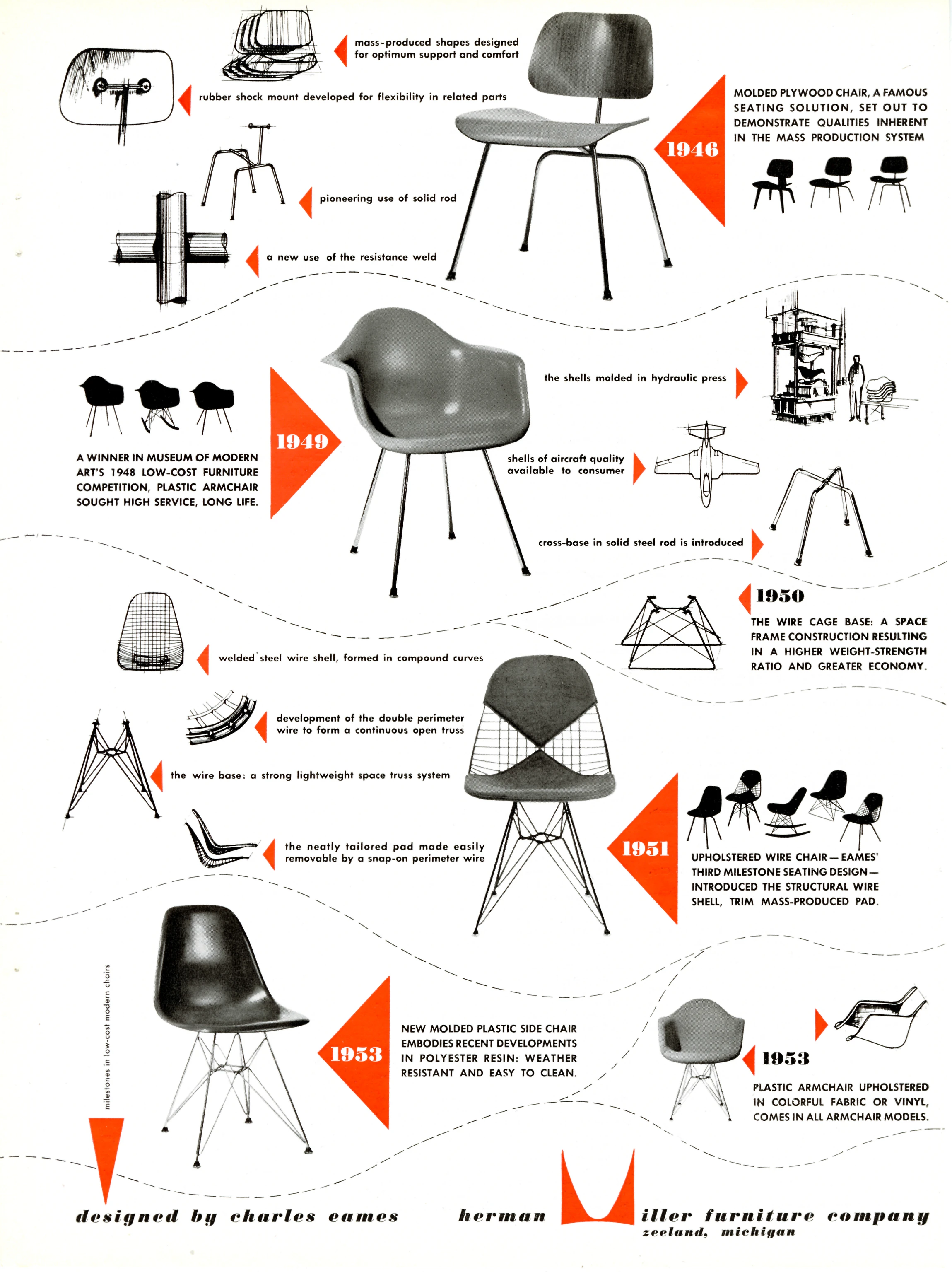

Twelve years passed between the initiation of the concept in 1940 and the production of the design in 1952—a remarkable period that also saw the Eameses realize some of their most enduring designs, including the plywood chairs and Case Study House. All throughout, they remained dedicated to their goal of creating a single-shell seat, driven by the notion that such a design could harness mass production capabilities (with fewer steps, fewer materials, and fewer connections) to deliver better value and service to the buyer.

On October 23, 1947, as the United States faced an unprecedented housing crunch in the aftermath of the second world war, the Museum of Modern Art announced The International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design. At an event hosted at New York’s Rainbow Room, René d’Harnoncourt, the museum’s ascendent director, explained its intent: “To serve the needs of the vast majority of people we must have furniture that is adaptable to small apartments and houses, furniture that is well-designed yet moderate in price, that is comfortable but not bulky, and that can be easily moved, stored and cared for; in other words, mass-produced furniture that is planned and executed to fit the needs of modern living, production and merchandising.”

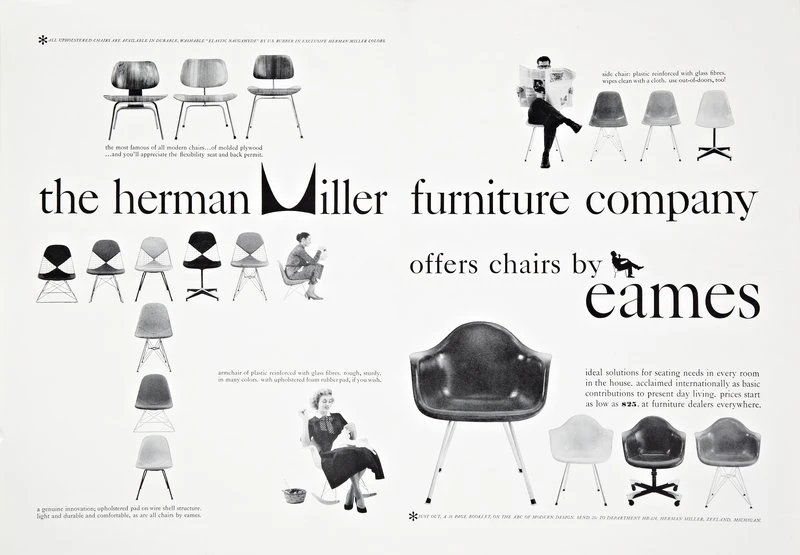

This photograph showing a range of chairs, parts, and bases was used on Entry Panel 7990a for MoMA’s International Competition for Low-Cost Furniture Design in 1948.

© Eames Office, LLC

The initiative echoed many of the same tenets that drove the museum’s 1940 Organic Designs in Home Furnishings competition and further blurred the institution’s lines between cultural instigator and savvy merchandiser. To mitigate some of the failings of the earlier effort—namely that the winning entrants failed to be successfully commercialized—the museum adopted two new strategies. Museum Design Project, Inc., “a non-profit organization set up by representatives of the trade,” was created to officially sponsor the competition and involve manufacturers from the outset. Secondly, in addition to the open competition, selected research teams were formed between leading designers and “technological laboratories” and awarded grants of $5,000 to put toward their ideas. For one of these teams, Charles Eames, having won (with Eero Saarinen) first prize in two categories in the earlier 1940 competition and been featured in a highly successful “solo” furniture exhibit at the museum in 1946, was paired with the engineering department at UCLA.

The team’s entry eventually consisted of four seating concepts, detailed on panels containing photographic documentation, technical drawings, specifications, cost analyses, and explanatory texts. The most speculative of the four designs—a large free-flowing lounge chair of indeterminate use produced from resin and fiberglass cloth stretched over a foam interior— came to be known as La Chaise (after the resemblance it bore to artist Gaston Lachaise’s floating figurine). As if created in direct opposition to this concept, the team also presented an experimental “minimum” chair designed to test the limits of material necessary for a viable seat. The remaining two entries, arm and armless single-shell seats made from stamped aluminum and steel set atop a variety of metal and wood bases, harkened back to the ideas for seating Eames and Saarinen had initiated in the Organic Design competition.

Ray and Charles demonstrate two of the many postures afforded by their La Chaise prototype, flanked by early stamped metal iterations of the shell chairs.

© Eames Office, LLC

That the Organic chairs never came to fruition offered Ray and Charles an invaluable lesson going forward: determining the technique and viability of manufacture was critical to the successful development of any design. In recognition of this (and the 1940 antecedents) the introductory text for the new chairs read “the form of these chairs is not new nor is the philosophy of seating embodied in them new—but they have been designed to be produced by existing mass production methods at prices that make mass production feasible and in a manner that makes a consistent high quality possible.”

Just as molded plywood had been adapted from other applications for use in furniture, the Eameses saw metal stamping (think car parts) as “the technique synonymous with mass production in this country” and believed it to be an operable solution for inexpensive furniture production. When securing the use of hydraulic presses at UCLA proved troublesome, the Eames Office set about producing the steel and aluminum prototypes in their Venice, California, shop using a drop hammer. However, the technique was anything but elegant (it consisted of dropping a 250-pound weight onto an aluminum or steel sheet sandwiched between two plaster molds) or effective (the molds usually broke after about three uses and it took around four drops to successfully mold each shape). The completed stamped metal parts were welded together to form a seat and then coated with either vinyl or neoprene to offer a more agreeable finish quality. Adapting another of the technologies developed for their plywood chairs, shock mounts (rubberized discs with an embedded screw thread) were affixed to the shells to enable a flexible and secure connection to the desired base.

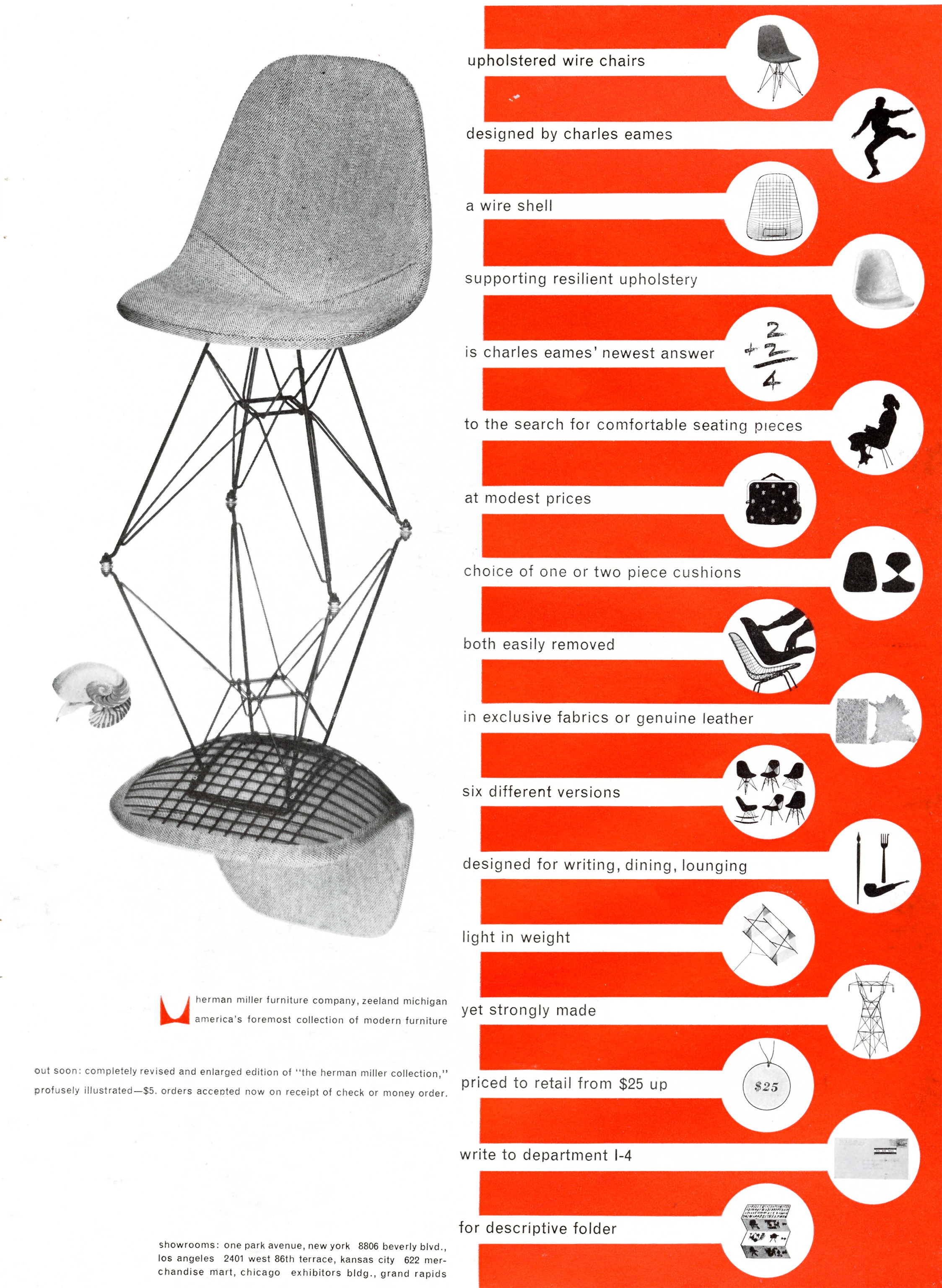

Staff member Don Albinson works on a fiberglass side shell. The appearance of the wire sofa and wire chair frame give some sense for the simultaeneous development of these designs.

© Eames Office, LLC

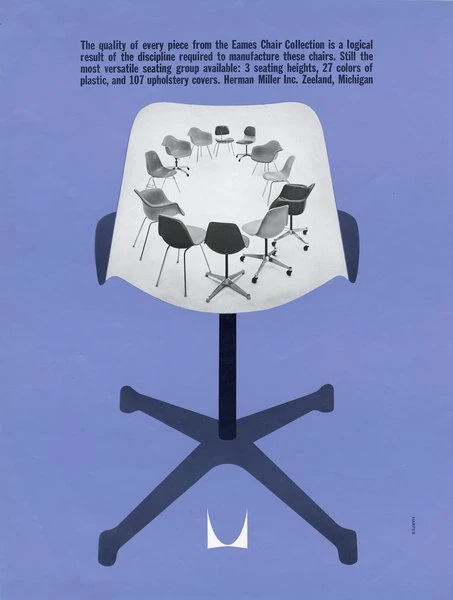

Even at this embryonic point in their development the chairs put forward an idea that would come to define Eames seating over the following decades—they were not being conceived solely as a product, but rather, as a part of a system. The same seat design could be applied to different bases to offer chairs of differing character or purpose. As the 1948 competition entry panels point out, depending on the configuration, the chair could serve as either rocking or dining model, or be utilized in living rooms or lecture halls. This modularity, coupled with the Eameses’ impulse to offer a universally pleasing form that would work in varying environments and be acceptable in large quantities, would set the stage for a runaway success.

For their efforts, in 1949 the Eames Office/UCLA team was awarded second place in the seating category by a jury that included d’Harnoncourt and Mies van Der Rohe. (Somewhat ironically, first place was granted to a design by Donald Knorr, a fellow architect and Cranbrook alum who was under the employ of Eero Saarinen.) As the Eameses further prepared the design for production, the mounting expense of the tools and machines required for manufacturing the stamped metal pieces proved to be prohibitive for Herman Miller, the company with whom the Eameses had entered an exclusive partnership to design and produce their furniture. The added steps of welding and applying a coating to the seat also pointed to potential inefficiencies that would further add to the final cost of the chairs.

The eventual answer to the quandary came in the form of another new material that had yet to make the leap from military and industrial applications into consumer goods: glass fiber– reinforced plastic. Working with a Los Angeles–based company called Zenith Plastics, the Eames Office devised a method that allowed them to make complex, three-dimensionally-formed shells with smooth surfaces in a minimum of working steps. The technique involved applying a molten plastic resin to a nest of glass fibers which were then sandwiched between positive and negatives molds on a hydraulic press resulting in a lightweight and extremely stable compound. While refinements were made to the finish quality, the self-contained process conformed to the Eameses’ preference for the honest use and representation of materials. Without further treatment or upholstery, the new fiberglass shells were comfortable to sit in and pleasant to the touch. By the time the winning entrants to the MoMA competition were exhibited in May 1950, in a show dubbed Prize Designs for Modern Furniture, the armchairs on view were produced utilizing the new technique.

Charles Eames and a staff member photograph DSS chairs at 901 Washington in June 1960.

© Eames Office, LLC

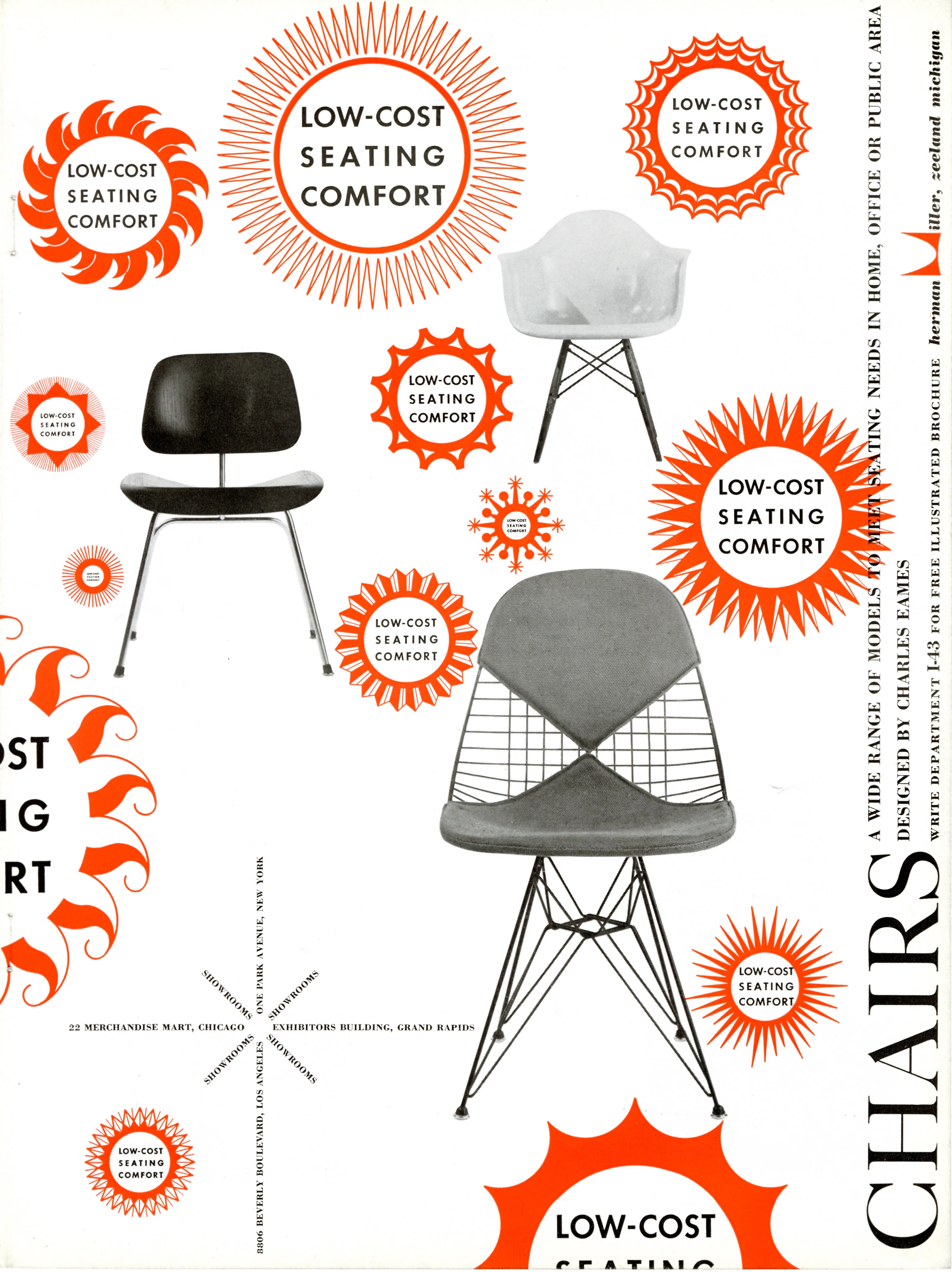

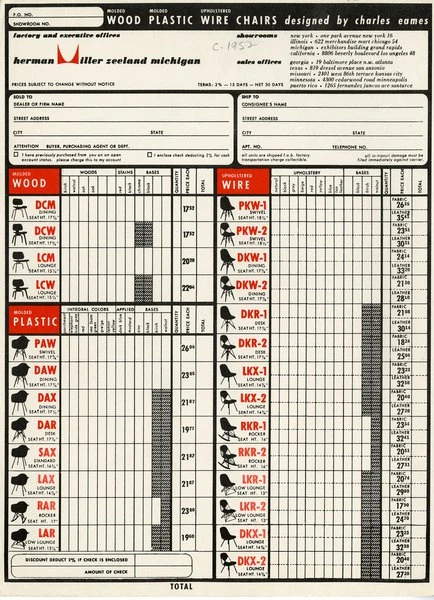

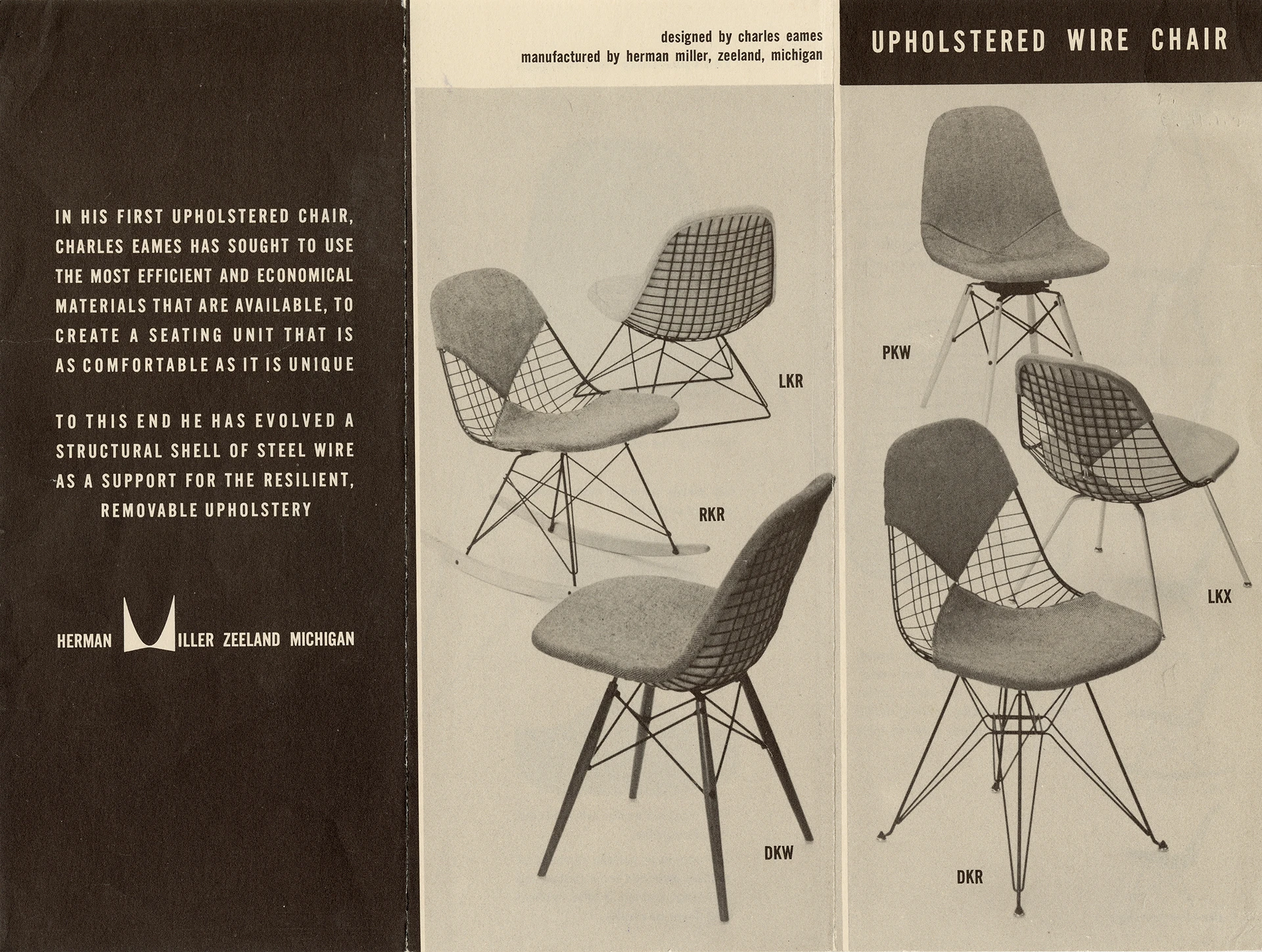

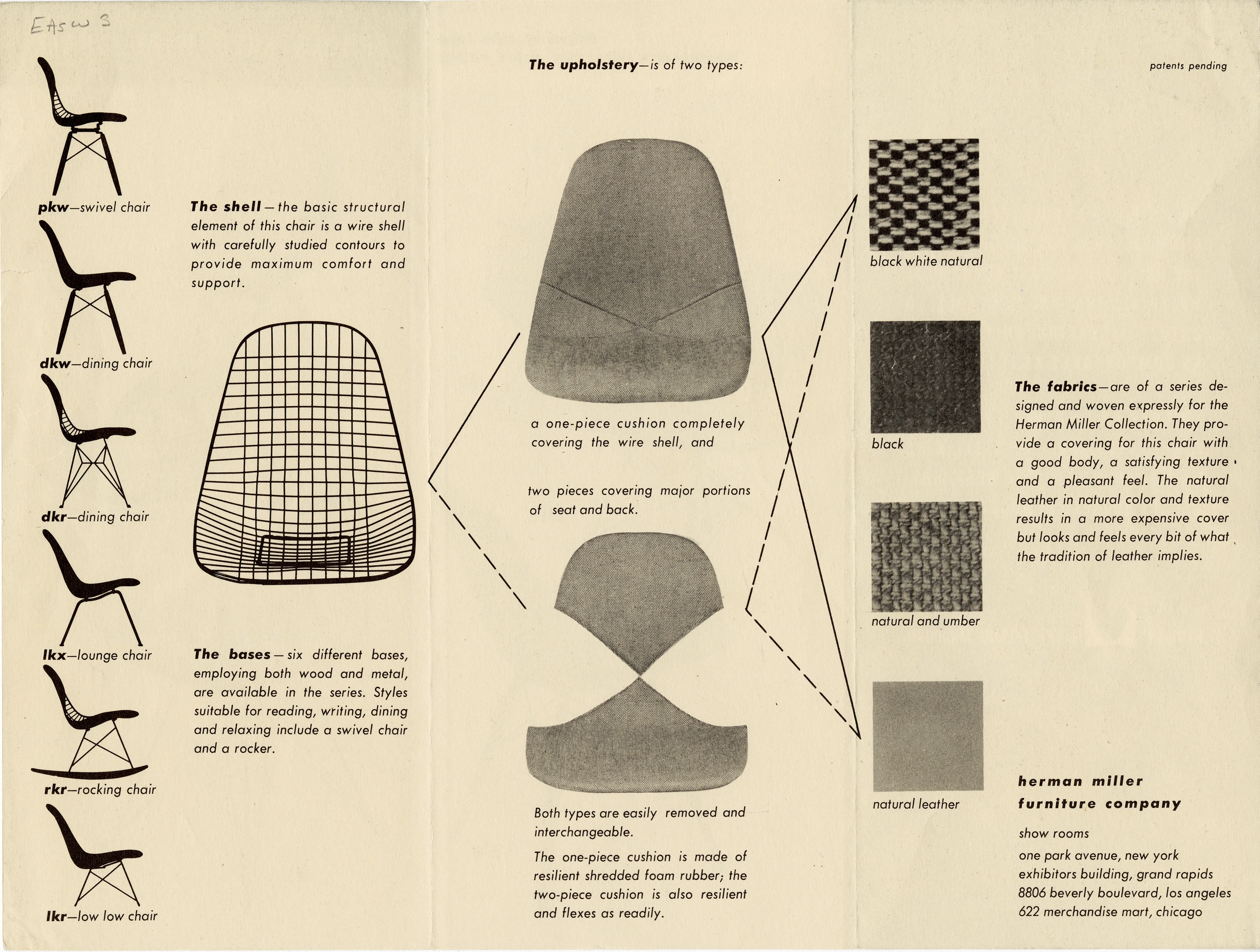

The Eameses and Herman Miller had initially approached the armchair believing it to be the more complex of the two designs. This initial supposition turned out to be erroneous as the arms offered an overall stability to the molded piece whereas the side shells were prone to flexing and cracking. The mass production of the fiberglass side shells proved to be so problematic that in the intervening period the Eameses were able to realize an entirely new design for the side shell in resistance-welded wire. The technique for wire rod construction was familiar to the office from various table and chair bases, and with some minor adaptations, proved to be successful for creating a durable and lightweight seat. Like its fiberglass counterparts, 1951’s Wire Mesh Chair adapted to a number of different bases (albeit without shock mounts) and offered a revolutionary approach to upholstery. The chair was conceived to accept easily replaceable one- or two-piece pads that accounted for only 10 percent of its total cost.

Eventually, by the end of 1952, the plastic side shell finally entered into production, closing a loop that had been opened over a decade earlier with Eames and Saarinen’s first single-shell side chair entry for the Organic Design competition. But as in many situations the closing of one door is the opening of another. The Eameses would continue to adapt and refine their design for the fiberglass shell to varying degrees for the rest of their careers. Or, as Charles told Home Furnishing Daily in 1969, “I really enjoy doing furniture, and I look at it as a kind of unfinished business.”

I really enjoy doing furniture, and I look at it as a kind of unfinished business.

Ray and Charles discuss the wire chair in April, 1970, three years after it was discontinued by Herman Miller.

© Eames Office, LLC