An Architectural Foundation

These little-known architectural designs by Charles Eames in St. Louis during the Great Depression reveal the seeds of his design ethos.

Before Charles Eames emerged as one of the most significant voices in 20th-century design, he was an architect, and he continued to call himself an architect whether he was designing a chair, a movie, an exhibition, or a building. He liked the fact that architecture implied both an attention to structure, and to discipline.

His best-known built project, the Pacific Palisades home where he and Ray lived (better known as Case Study House #8, or the Eames House), remains a modern marvel that draws tourists from around the world. That project, and other elements of Charles’s working methods, have roots in six somewhat inconspicuous buildings that he designed in his native St. Louis during the Depression. These lesser-known—indeed, mostly forgotten—structures may not show the seasoned artistry of Charles’s later years, but their subtle details and thoughtful layouts reveal a designer committed to aesthetics and attuned to the people who would inhabit his spaces. The six residences—and a church where he designed several key elements—foreshadow Charles’s artistic development, and eventually led him to Cranbrook, the design academy that catalyzed his career.

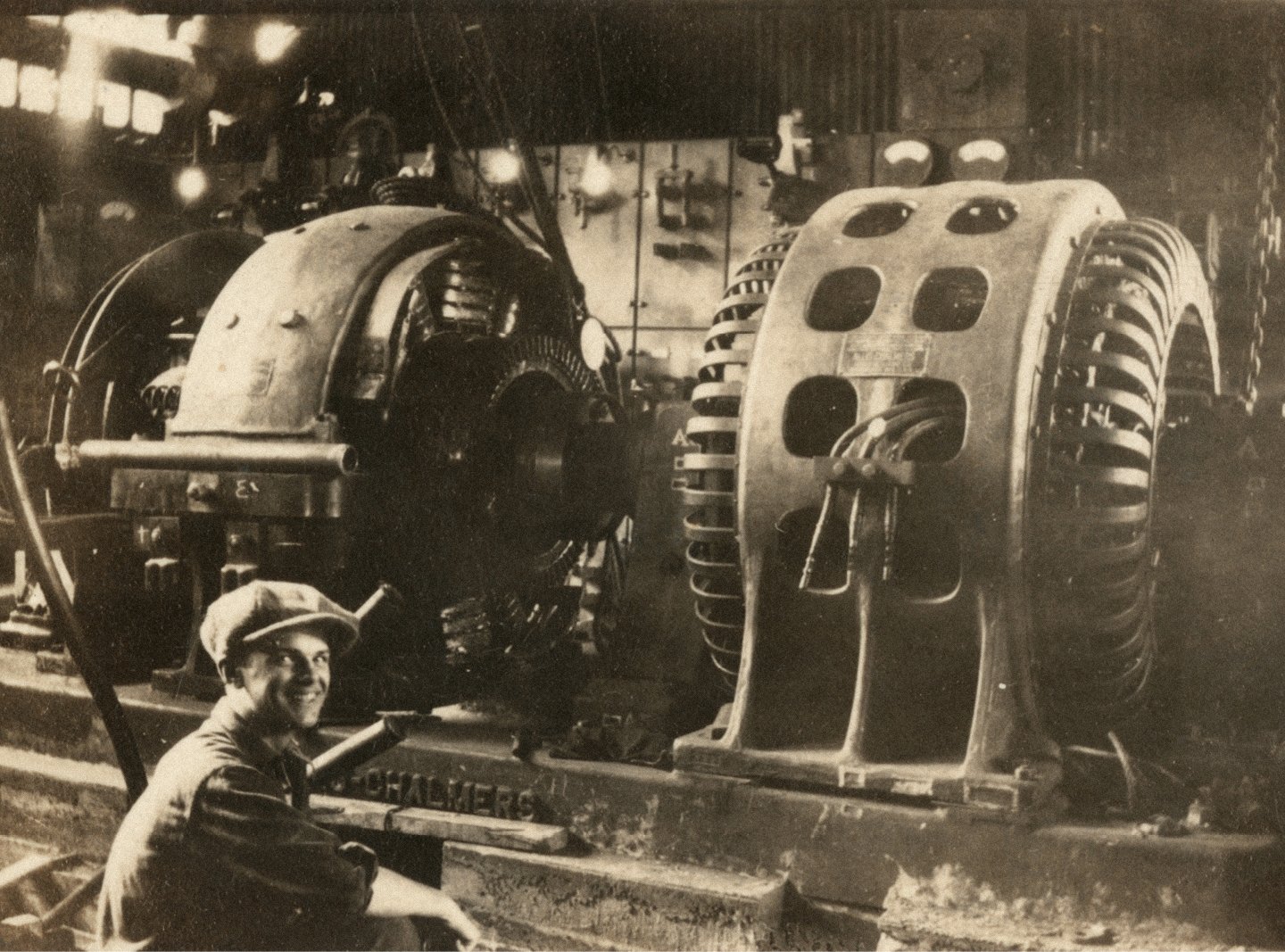

Born in 1907, Charles began working to help support the family at age 10, first at a printing shop and later in high school at a steel mill located in Venice, Illinois, across the river from St. Louis. His milieu sounds grim, but his supervisors soon discovered his propensity for drawing, and assigned him drafting and engineering duties. He eventually won a scholarship to Washington University’s architecture program, where the faculty were religiously devoted to a curriculum focused on the then-reigning Beaux-Arts orthodoxy. Charles, obsessed with Frank Lloyd Wright, refused to embrace the ethos; similarly, later in his career, he would also resist arbitrarily imposed design solutions. He was dismissed from the school after his second year.

Charles Eames at the Laclede Steel Company in St. Louis, where he worked to support his family. This photo was taken in 1923 when Charles was sixteen.

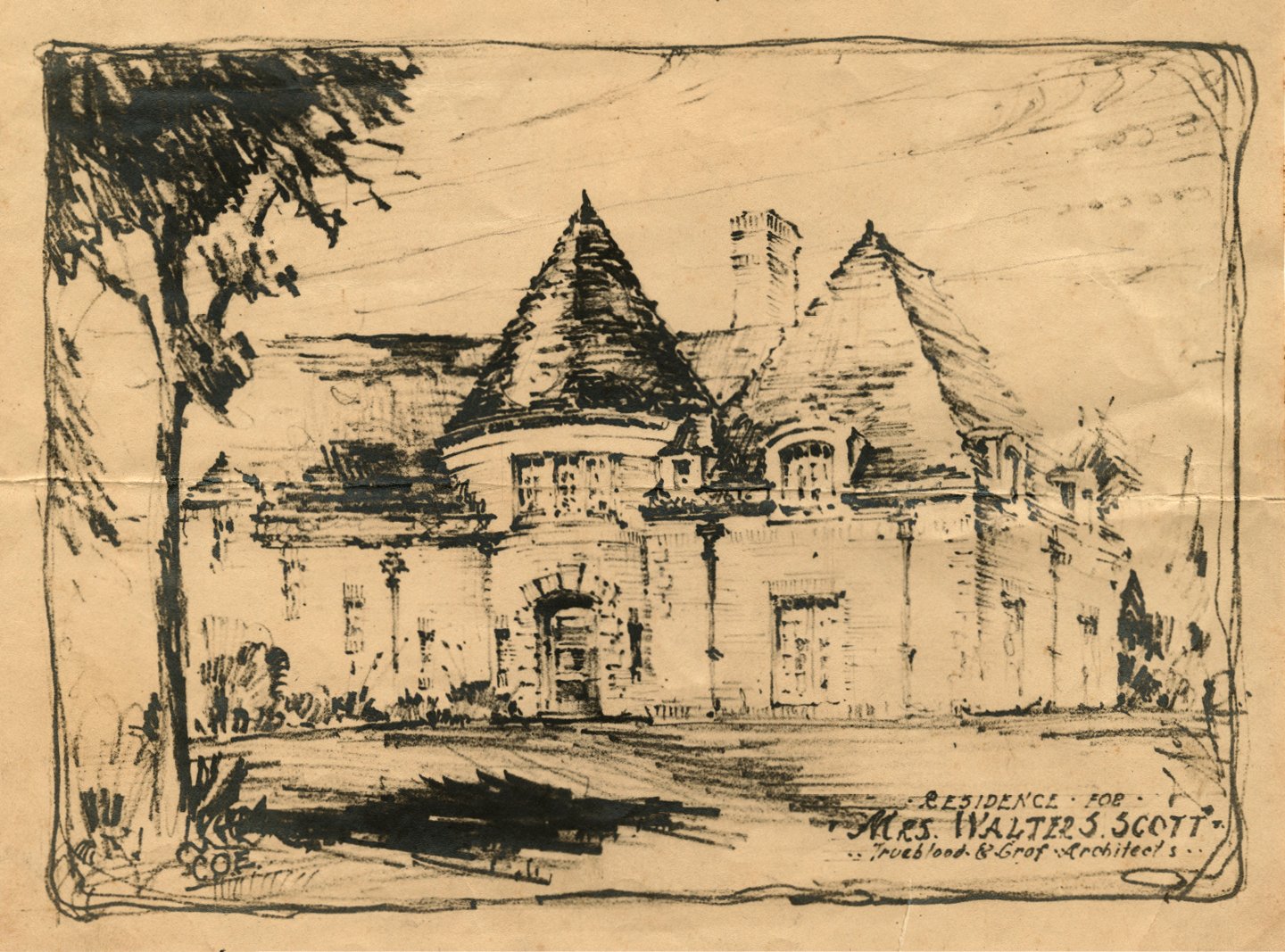

Charles drew this when he was on staff at Trueblood & Graf, where he worked before attending architecture school. His mother saved it in a scrapbook.

The antipathy towards Charles was so extreme that the school’s dean, architect Gabriel Ferrand, even tried to poison the well with Charles’s future father-in-law. When Charles was courting Catherine Woermann, who was training to be an architect herself, Ferrand told her father that Charles “would never amount to anything as an architect,” according to author Pat Kirkham in her book, Charles and Ray Eames: Designers of the Twentieth Century. Yet a year after Charles and Catherine were married in 1929, he co-founded an architecture firm, and began receiving commissions for single-family homes and churches, including two in Arkansas.

His father-in-law’s company, Woermann Construction, built many of them, but Charles was involved in every aspect. In those lean times of the Great Depression, architects were often expected not just to draw blueprints, but to actually help build the buildings, as well as design the lighting, carve the sculptures, and supply the furniture. This mode of working—through which Charles connected with numerous artisans—fit into the Gesamtkunstwerk approach, as espoused by Eliel Saarinen, in which the architect creates everything for a commission, down to the last detail. As Charles told Virginia Stith in An Eames Anthology, “We designed a lot of the rugs and the furnishings for the [Meyer] house. I designed the rugs and the tile, and that’s really when I became closely acquainted with the Saarinens—I … had Loja Saarinen and her group weave the rugs I had designed.”

Charles built a press to print his own lithographs and etchings, such as this one, entitled 12th and Chestnut. He often used St. Louis architecture he admired as subject matter.

Charles produced the majority of his etchings and lithographs during the years 1927–1932; many convey his passion for architecture.

While this work fulfilled him for a time, Charles would eventually abandon the craft. “Designing a whole building is just too demanding of attention to keep the basic concept from disintegrating,” he told a reporter for the Associated Press. “Builders, prices, materials, so many things work toward lousing it up.” But his architecture skill set served him his entire life, helping him enact his visions more precisely in arenas like furniture design, film, and photography. As Charles observed in 1974, “I don’t think it would be any exaggeration to say that … the things that we have done long ago and recently wouldn’t be the way they are, if we weren’t architects.”

Though Charles’s early St. Louis work is poorly documented, the six homes and one church he designed there have been beautifully maintained. In this overview, St. Louis architectural historian Esley Hamilton helps provide perspective to understand how Charles’s design philosophy developed in the 1930s.

Skelly House, 1932

From afar, early Eames houses tend to resemble their neighbors; only upon closer inspection are their unique details revealed. Built around 1932 for Gray, Eames & Pauley, this stately Tudor Revival near Washington University boasts fine brickwork, like the rows of “soldier courses” between the foundation and ground floor (and in other parts of the house), so named because the vertically positioned bricks “stand up,” like soldiers. St. Louis had long been known nationally for its fine red brick, forged by enslaved and immigrant workers using the rich clay deposits in the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers confluence nearby. The curved bricks near the Skelly House roofline were likely fired specially for the project. “Bricks are like loaves of bread,” explains Hamilton. “The outer part is a crust, and when you cut that away, it makes the brick less stable.” St. Louis’s skilled brick masons excelled at producing these types of bespoke features.

Built on a corner, the home was designed to have its best sides facing the street, which meant hiding the garage around back. Boulevard-facing garages were strictly gauche at the time of construction, Hamilton notes, adding that after they became popular following World War II, many subdivisions banned them. The Skelly House’s second story terrace with French doors is likely original, as is the handsome, custom-made oak front door. Many of its first-floor windows feature “leaded glass” in a diamond pattern—small pieces of glass joined together with lead, rather than the more common boxy, wooden configurations.

Sweetser House, Circa 1932

World War I veteran and Washington University civil engineering professor Ernest O. Sweetser commissioned this University City home around 1932. He and his wife attended Pilgrim Congregational Church with Eames, who designed the house with his partner Charles M. Gray. The home boasts an eye-catching, colorful brick pattern, particularly in its stunning, front-facing chimney, which has red, gray, and blue bricks as both “stretchers” (the long side of the brick faces outward) and “headers” (the short side faces outward). “This design is a good indication that a building is brick structurally, and not just a veneer,” says Hamilton.

Unlike the area’s prevailing Colonial Revival model, the Sweetser House is asymmetrical, with just three bays, and the front door off-center. The detached garage is likely original, and owners subsequently added an addition. More modest than the Skelly House, it’s nonetheless thoughtfully designed and, at the time of construction, its interior featured “classical style coverings, oak floors, and bookcases in arched alcoves with wood keystones and moldings in the living room,” writes design historian Pat Kirkham. The home also has shutters that actually open and close—in contrast to faux, non-functional “shutters”—moored by “S”-shaped anchors that hold them in place. They can darken a room, and are especially helpful if a bad storm rolls in. “That’s the difference between a classy building and a tacky building,” adds Hamilton, “whether the shutters are real or fake.”

Pilgrim Congregational Church, 1932-1937

In 1929, Charles and Catherine were married at Pilgrim Congregational Church, then known as the city’s “white glove” outpost of the Protestant denomination. The church sits next to the architectural gems of Soldan High School and the St. Louis Artists’ Guild former home, on what many considered “the most beautiful streetscape in St. Louis,” says Hamilton. Featuring a theater-style auditorium that seats 1,000, Pilgrim was constructed of pink granite in a Modified Romanesque style in 1906 by the firm Mauran, Russell & Garden, who also designed a church for Unitarian minister William Greenleaf Eliot, co-founder of Washington University and grandfather of T.S. Eliot.

In 1932, Charles was commissioned to design three sets of new oak doors for Pilgrim’s narthex, which open onto the auditorium and feature an octagonal pattern and stained glass insets, which Charles produced with the renowned glass maker Emil Frei. (They are seemingly devoid of religious significance.) Charles also designed the stained-glass transoms above the doors, in a pattern of crosses and X’s.

The implementation of these doors was delayed by one year, however, during which time Charles had made an enormous, brass, cross-shaped chandelier for Pilgrim’s chancel, more Catholic than Protestant in its imagery, which was modeled on a chandelier in Venice, Italy’s Basilica of San Marco. When Pilgrim’s lofty tower was struck by lightning in 1935, Charles reimagined the spire as a lower pyramid, and rebuilt the roof in less flammable material, adding a lightning rod to be safe.

Meanwhile, Charles also designed a pair of churches in Arkansas, including the stunning St. Mary’s Church in Helena, which caught the eye of Eliel Saarinen, the father of St. Louis Arch designer Eero Saarinen. Eliel offered Charles a fellowship at Bloomfield Hills, Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy of Art, where he met Ray and launched the design movement that made them famous.

As for Pilgrim, Charles’s renovations have held up beautifully, as has a flourish he added in 1937: a whimsical “Pilgrim Congregational Church” sign out front, which is made from copper, and lights up from the inside. In 1953, long after Charles left the region, the church became St. Louis’s first integrated Protestant church, Hamilton says, and maintains a diverse membership today.

Dean House, 1936

Perhaps what Charles was envisioning while clashing with his Washington University professors, the Dean House is an important home in the annals of early St. Louis modern architecture. Yet Charles and his partner Robert Walsh imagined something more modest: a moderately-priced “modern interpretation of the little French town house,” according to an archived note.

The house was built in 1936 during the depths of the Depression, but a pair of recently constructed modernist office buildings nearby likely emboldened Charles in his efforts to experiment. Built in well-to-do Webster Groves, southwest of St. Louis, the Dean House must have been a curiosity, featuring art deco stylings like a V-shaped chevron pattern on the front door and curved railings on the side porch steps.

Still, its look is not a total departure from his previous efforts, and doesn’t approach the audacity of his hero, Frank Lloyd Wright. The emphasis is still largely on the brickwork, for example, by way of dentils and first floor quoins. (The white paint on the home’s exterior is likely not original, suspects Hamilton.) Nonetheless, it showcases evolutions in Charles’s style, including the corner windows that are framed in metal, the flat cornice, and the low-pitched roof. Unlike his University City homes, the chimney is not an exterior design feature. If not audacious, it’s certainly a house that offers some intrigue.

Dinsmoor House, 1936

The Colonial Williamsburg craze was sweeping the nation when the Dinsmoor House was built in 1936, with eighteenth-century Williamsburg, Virginia, having been reimagined as a tourist district not long before. As such, this Georgian Revival home in Webster Groves is more of a look backward than a look forward. Based on a Virginia plantation house called Carter’s Grove, the Dinsmoor House has a hitching post in the front, and came outfitted with furniture meant to recall the colonial era. (The home’s patron, it turns out, collected furniture from the 1700s; certainly none of it would have been as comfortable as an Eames chair.)

Dinsmoor’s then-fashionable hipped roof doesn’t hang over the sides, and its door frame is particularly elaborate, with a “broken pediment” above the doorway showcasing an urn. Why an urn is unclear. The frames surrounding the windows have several layers of molding, and the windows themselves go almost all the way to the floor, perhaps suggesting they were designed to de-emphasize low ceilings. The home isn’t on a particularly large piece of land, perhaps necessitating the front-facing garage, which has an extra room above it, behind dormer windows.

Morris House, 1937

A “phony colonie” with only glancing details suggesting inspiration from Colonial architecture, the Morris House also showcases scant Eames influence. Approached from the street, the home, which was built in 1937 by Eames & Walsh, immediately feels off; it seems to be rotated on its side, seemingly wedged into a smaller plot than its neighbors. But it is much deeper than it is wide, making the square footage comparable to nearby homes, and upon close inspection bears certain charms. The moldings around the front door and windows, the quoins on the corners, and the corner windows all recall other Eames St. Louis projects. In November, the current owner was having the previously white home painted a dark “Mount Etna” color, and noted that she could hardly believe it was an Eames house when she first learned about it. “I think he was just trying to make some money,” she speculated with a laugh, noting that her family nonetheless loves living there. “It gets so much light!”

Meyer House, 1936-38

Charles’s other St. Louis–area homes are in upper middle class neighborhoods, but the Meyer House is right across the road from former Anheuser-Busch CEO August Busch IV’s mansion in Huntleigh, perhaps the region’s toniest enclave. The best known of Charles’s early homes, the Meyer House represents a crossroads in his life, a transition from more traditional craftsmanship to the experimental style he’s known for.

Upon approach, what’s immediately noticeable are the low-pitched roofs, aluminum windows, and the home’s massive scope. Its 7,200 square feet include five bedrooms, sprawling decks, servants’ quarters, a library, and a wine cellar. The home’s steel-reinforced exterior is formidable, but has fanciful details like gargoyles, a pewter sundial, and bricks carved with musical notes from a Mozart symphony (Number 40 in G Minor).

One of the area’s first air-conditioned homes, its aluminum sash windows were also a new technology, but the property isn’t as Charles originally intended. In fact, his first set of plans, nine months in the making, were rejected by the couple who commissioned it. “I can’t remember why, now, but they just weren’t what we wanted,” Alice Meyer (then Gerdine, after a subsequent marriage) told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1982.

They accepted a second draft of the design, which Eames took with him to Cranbrook in 1936, at which time Eliel Saarinen also made significant edits, changing certain “very traditional” elements, like the dining room niches, to make them “much more interesting,” Gerdine said. Originally, the living room was painted pink, with gray drapes designed by Saarinen’s wife Loja, and rugs and tile designed by Charles himself. The interior influences range from art deco to Scandinavian modernism to Georgian Revival, and the countless bespoke features include a silver-leaf ceiling in the entrance hall, built-in bookshelves and art display cases, clamshell door pulls, and planters in the breakfast nook’s windowsill. ❤

Ben Westhoff is an award-winning journalist who has written for the New York Times and other publications; his new book is Little Brother: Love, Tragedy, and My Search for the Truth.

Elisabeth Moch is an illustrator based in Berlin. Her work can be seen in the New York Times, Wallpaper*, Apartamento, and Zeit Magazine, among others.

Andrew Raimist is an architect, writer, and photographer based in St. Louis, Missouri.

At Kazam! Magazine we believe design has the power to change the world. Our stories feature people, projects, and ideas that are shaping a better tomorrow.